Project Team:

Dragana Maksimovic, Karolina Malec, Antonia Muszi, Bernadette Pößnicker, Katharina Rauch, Vanessa Stöckel, Stefanie Weber

Concept

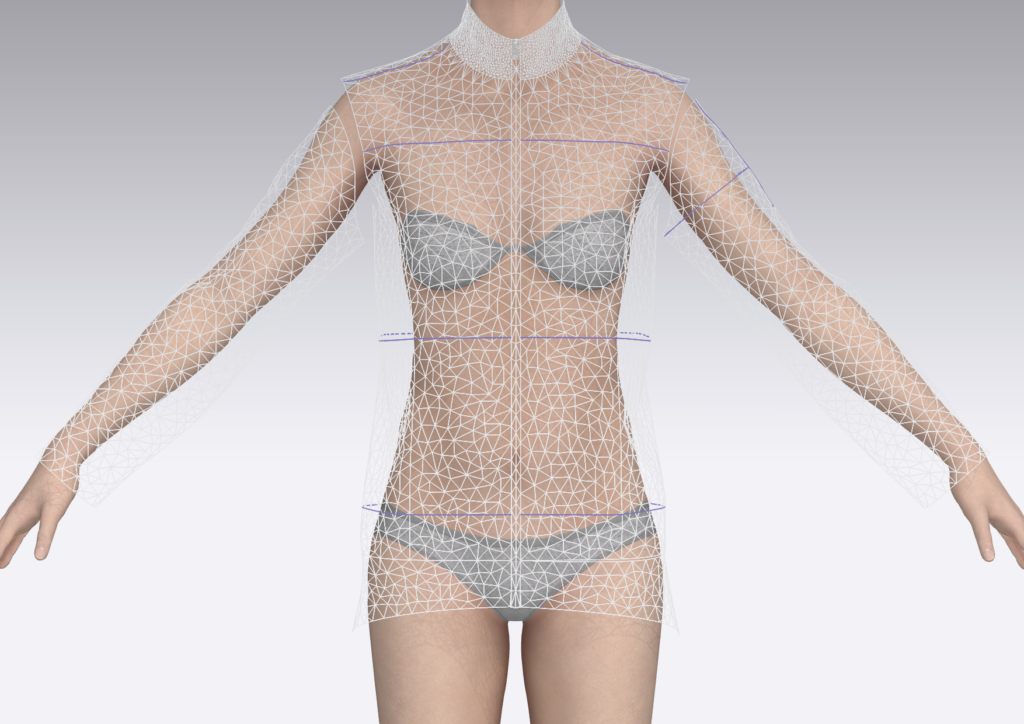

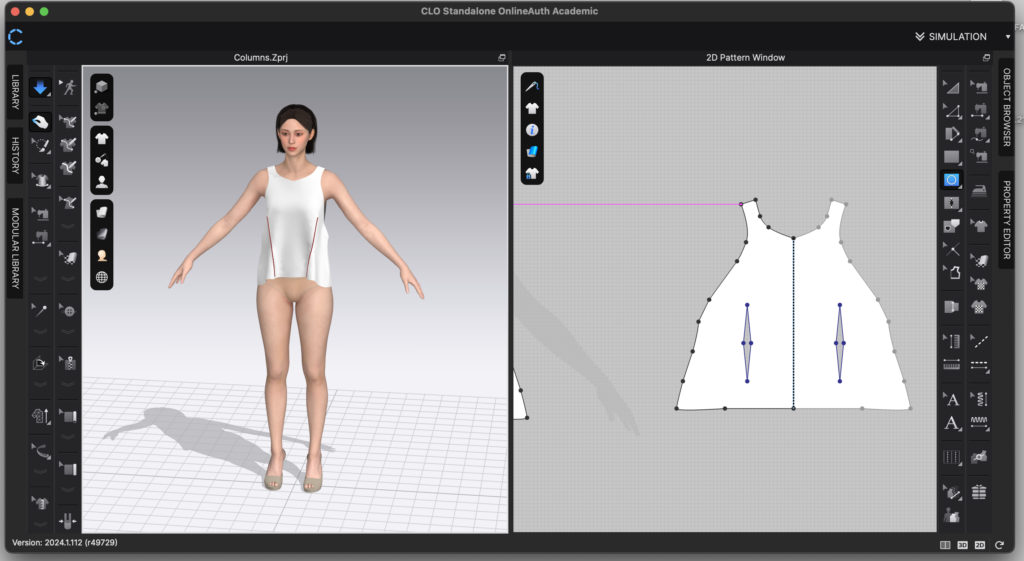

Luminous Flora is a captivating, interactive installation that invites visitors to create their own personalized flower arrangements, combining creativity with advanced technology. By using a tablet interface, participants can select and arrange virtual flowers, choosing from various colors and shapes to craft a unique bouquet. The flowers are carefully designed in a 3D program, ensuring that they feel life-like, with textures, colors, and shapes that bring them to life in a digital space. The final creation is then projected onto an abstract custom-made polygonal bouquet, which adds a tangible, three-dimensional aspect to the digital design. This process not only merges art and technology but also empowers participants to explore their creative potential in a completely new way.

The original idea for this project was to collaborate with Blumen B&B, a florist business located in Eggenberg. The goal was to offer an innovative and engaging way for customers to interact with floral arrangements. Visitors could experiment with designing digital bouquets that reflected their personal tastes, providing inspiration for real-world bouquets. This interactive experience was aimed at sparking new ideas and interest in floral design, with the hope that visitors would translate their digital creations into real-world purchases. While the project’s initial concept also included printing a tangible version of each digital bouquet, this was eventually left out due to logistical challenges. Instead, the focus remained on the interactive and immersive nature of the installation, offering visitors a creative and engaging experience through digital technology.

The project highlights the fusion of art and technology, showcasing how digital design can be used to create an interactive, visually stunning experience. Through the use of a tablet interface, participants design their bouquets and see them projected in real-time onto a physical abstract flower bouquet. The app, developed using Protopie and Figma, served as the primary interface for user interaction, and the mapping and projection of the floral designs were achieved with the help of Resolume, ensuring that the digital flowers blended seamlessly into the physical object. The communication between the app and the projector was achieved using OSC messages, enabling the projected design to update in real-time as the user interacted with the tablet interface. This seamless integration of digital and physical elements created a unique experience.

Software and Tools:

App: Figma & Protopie

3D Flowers and Animations: Blender and Adobe After Effects

3D Flower Bouquet Model: Blender, Adobe Illustrator, Lasercutter

Mapping and Projection: Resolume

OSC Messages: Interaction between App and Projector

Physical Setup: Flower Bouquet Sculpture, Bouqet Stand, Bouqet Vase, Beamer Stand, Tablet Stand

Hardware: iPad, MacBook, Beamer, external router, HDMI Cables, power Cables

Project Workflow:

Concept Development

Design Process (App, 3D Flowers, physical Bouquet)

Software Implementation (Protopie, Resolume)

Construction of the Flower Bouquet Sculpture

Construction of the stands

Testing

Hardware Setup

Troubleshooting

Final Adjustments

Supervising and Restarting the Installation during the exhibition

Evaluation

Challenges and Solutions:

Communication and collaboration issues within the group

Technical issues with video rendering and file sizes

Overheating and insufficient airflow for MacBook (and Beamer)

Network connectivity problems (fixed with external router)

Reflection & Challenges

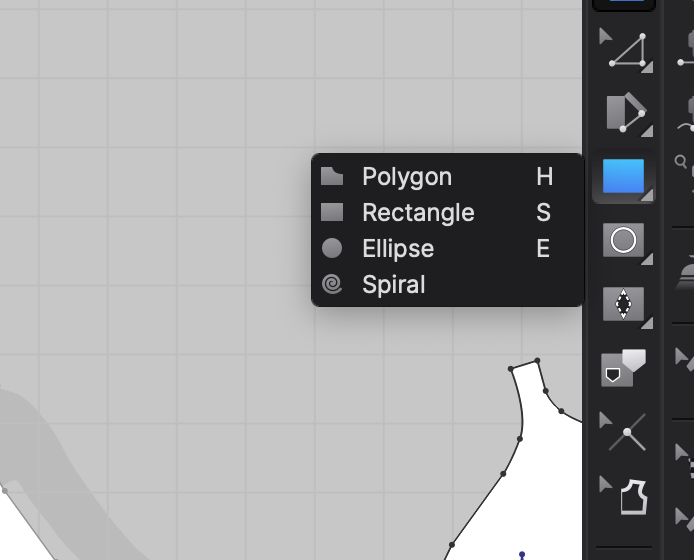

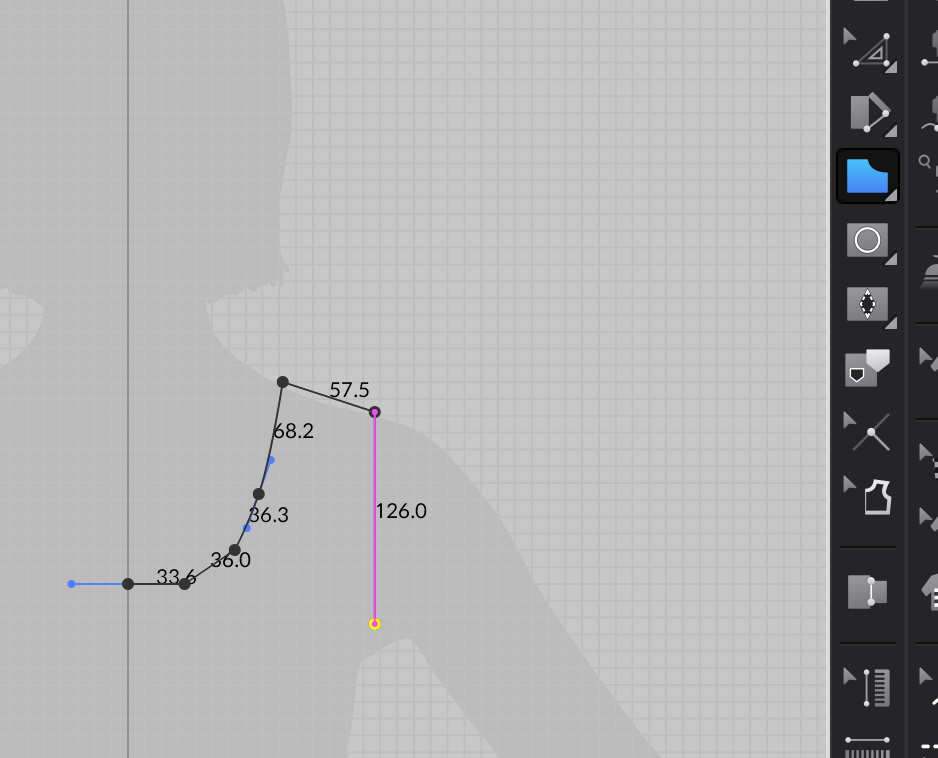

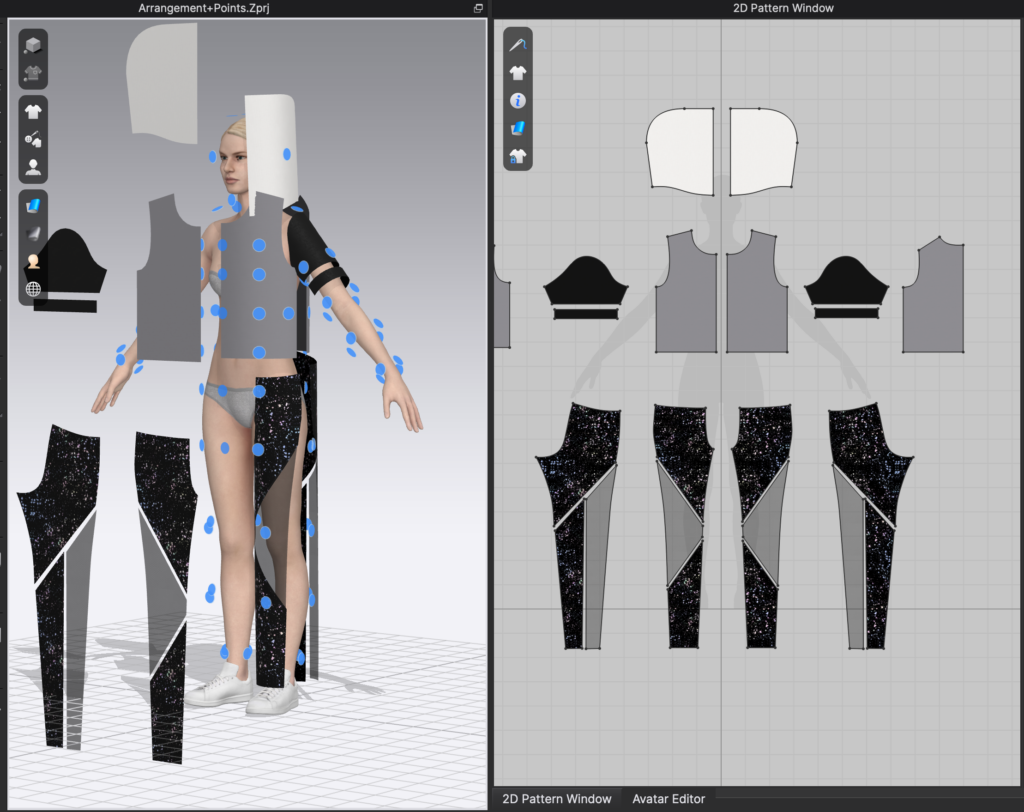

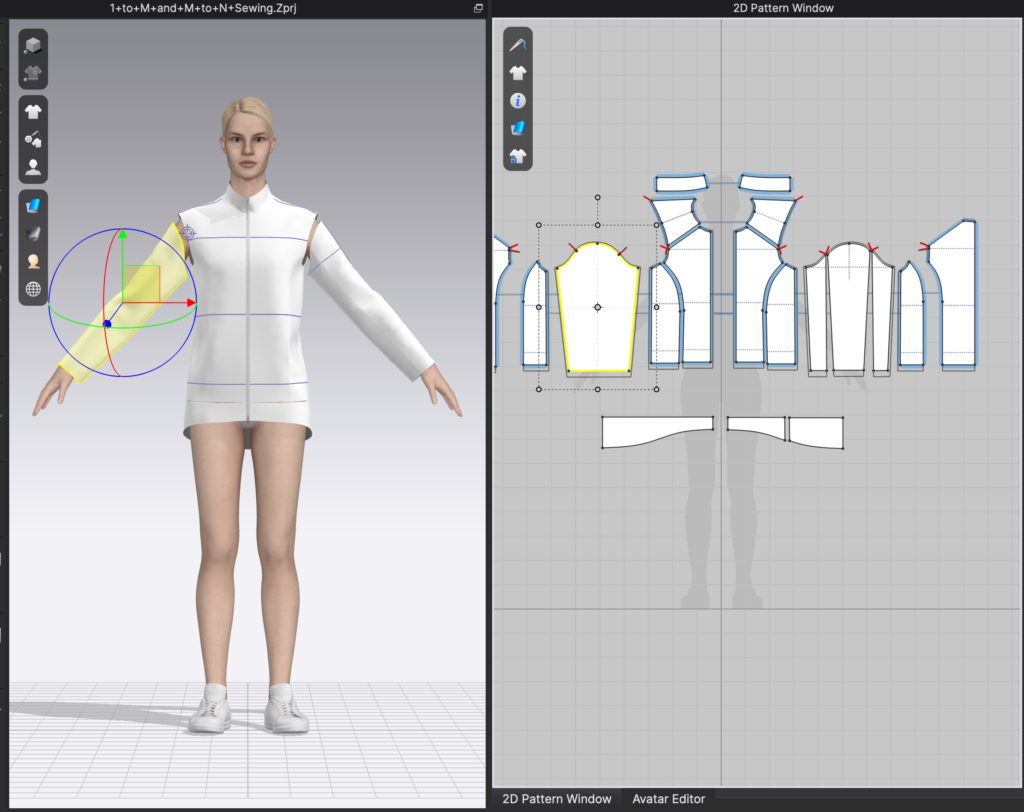

The development and execution of Luminous Flora involved multiple technological and artistic components. The app, which was created using Figma and Protopie, served as an intuitive interface for visitors to design their virtual bouquets. Through a drag-and-drop system, users could select flowers designed in Blender and After Effects, then customize them by changing colors and positions. These virtual bouquets were mapped and projected onto a custom-made polygonal 3D flower bouquet, which acted as the canvas for the projections. The Resolume software was used to map the flowers onto the physical structure, with OSC messages facilitating the communication between the tablet and the projector.

The flower visuals were created mainly in Blender, as the software was used to model the flowers, creating texture, animating the dancing light and rendering the PNG sequences. Each of the three flowers has been rendered in four different colors and from two different camera perspectives. We rendered the PNG sequences in a small resolution (one third of full HD) as suggested in one feedback session. Nevertheless the rendering of the 24 (short) videos took a lot of time as the computer rooms at FH are meanwhile unfortunately locked during the holidays and we used our private laptops. After rendering the sequences we went on to place the flowers into the triangles of the polygon flower bouquet. We used an SVG of the UV unwrapped polygon structure in Adobe After Effects and placed the flowers. To create additional movement and dynamic we added multiple light effects and movement effects onto the videos. At first we rendered the resulting videos in 4K which we discovered later was unnecessary and used full HD videos for the final installation.

The lowpoly bouquet was scribbled by hand and then built in Blender as a 3D model. Based on this model we built the polygon shaped flower bouquet out of bookbinding cardboard. For it to become the lowpoly sculpture in the end, we used the laser cutter to cut different pieces, mainly triangles. These pieces would then fit together in the end to form a big polygon. In the beginning we made latches in order to glue the pieces together. The latches were also a couple millimetres thick and made the shapes not fit together in the end due to their added height. Therefore we had to cut the latches off by hand, and laser cut additional small latch-like pieces with which it was possible to connect the shapes together on the inside. After constructing the sculpture the 3D model for the app was adjusted to the real life model, so the exact same shape is shown in the app.

The physical setup was also an essential part of the experience. A dedicated stand for the tablet ensured that users could interact with the app comfortably, while at the same time it served for the beamer, allowing an optimal positioning of the projections. The polygonal flower bouquet was placed on the opposite and in the center of the room, creating a focal point for the projections and adding depth to the digital designs.

As with any complex project, there were some challenges that arose throughout the development process. One of them was the communication within the group. Since it was a large group and each team member (each major) was responsible for different aspects of the project (e.g., app development, building the polygon flower bouquet, 3D flower design, mapping), we experienced moments where the lack of clear role definitions led to confusion and delays for some people in the group.

From a technical perspective, we faced rendering challenges related to the size of the files used in Resolume. Due to the large number of animations and video files required for the projections, we encountered issues with file sizes that were too large for the software to process efficiently. However, by compressing and converting the files into formats compatible with Resolume, we were able to resolve the issue and maintain the quality of the visual experience. Additionally to avoid reaction errors while dragging the flowers into the different triangle shapes in the app, a good solution would have been to make the entire triangular area in the app responsive, rather than just a selected part.

Another technical problem that arose was the overheating of the MacBook used to run the app and projection system. The stand was not optimal designed for that, leading to insufficient airflow and causing it to overheat. While we managed to temporarily solve this issue during the installation, better planning regarding ventilation and device placement and/or choice is necessary for future setups to avoid overheating. In addition, we faced network connectivity problems when the app was running through the cloud. The Wi-Fi signal was weak, which caused delays in communication. This issue was resolved by using an external router, which significantly improved the connection and allowed the system to function smoothly.

Despite these challenges, the final result was a great success. The project provided an engaging and visually striking experience for participants, combining creativity with technology in a way that encouraged exploration and interaction. The projections were seamless, and the digital bouquets were vibrant and life-like, enhancing the immersive nature of the installation. While there were moments of frustration and technical difficulties, the outcome exceeded our expectations.

Looking back, we recognize that some of the challenges could have been addressed earlier in the process. However, the overall experience was immensely rewarding, both for the team and the visitors. The project allowed us to blend traditional floral design with cutting-edge technology, creating a unique and memorable interactive installation. The envisioned collaboration with Blumen B&B added another layer of relevance to the project, linking the digital and physical worlds of floral design.

Pictures of the final installation: