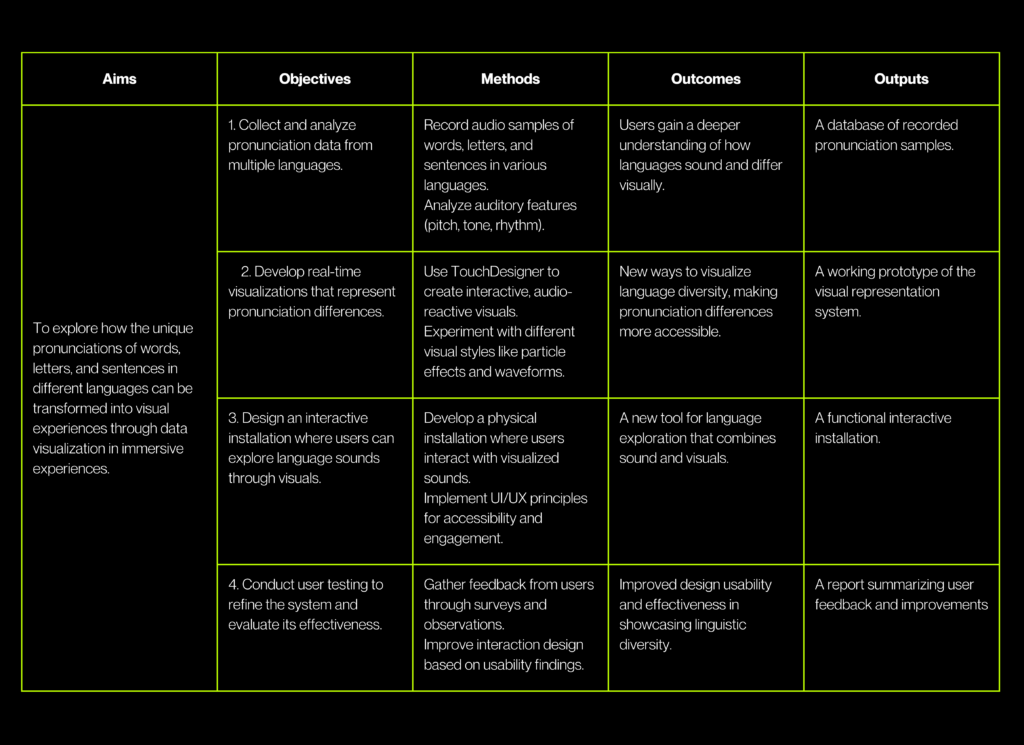

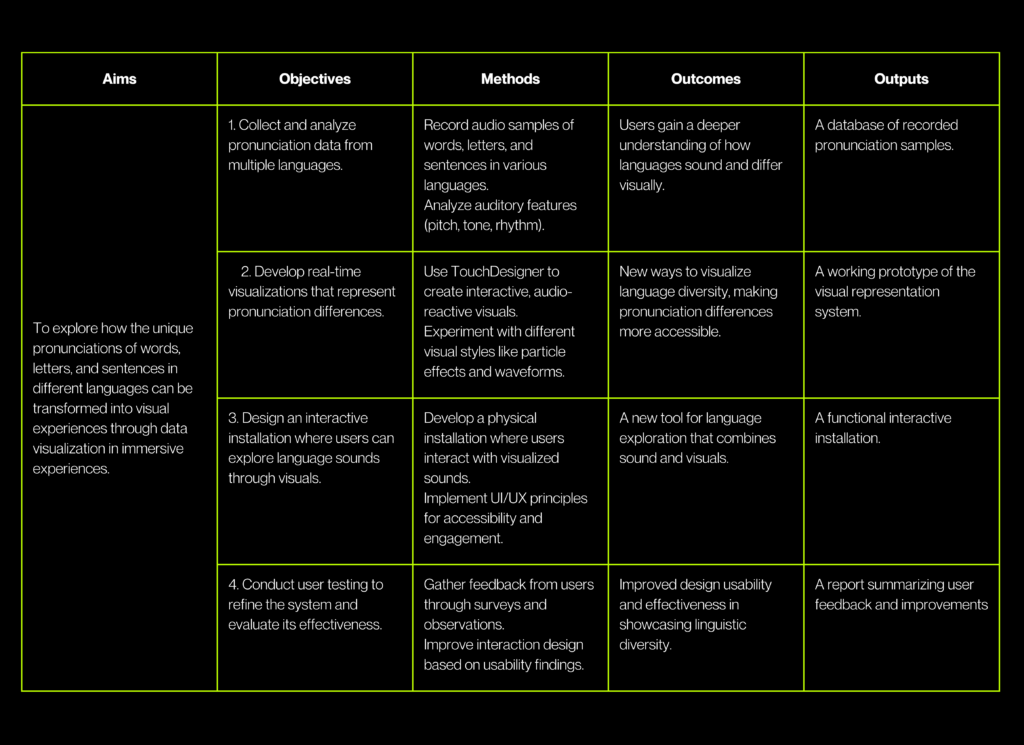

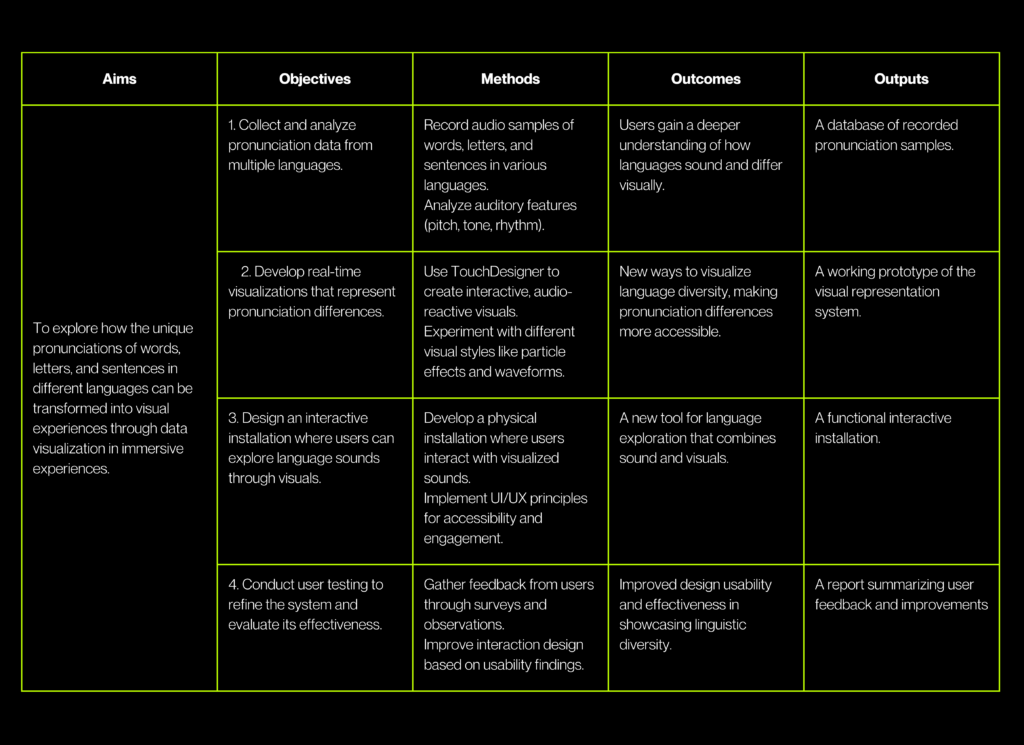

Research Matrix

Feedback

This week was all about feedback. After months of deep diving into research, I had the chance to discuss my master’s thesis progress with three different experts, each offering a unique perspective on my work. These conversations helped me reflect on where I am, what I’ve accomplished so far, and most importantly where I should go next.

First Round: Structuring the Next Steps

On Wednesday, I had a meeting with Ms. Ursula Lagger, who guided us through our master’s thesis proseminar this semester. Our conversation focused on my exposé, my current research state, and my plans moving forward. While I have already done a lot of research on the theoretical background, she emphasized that now is the time to shift towards the practical aspects of my work. One of the biggest takeaways from this meeting was the importance of structuring my prototyping phase. She encouraged me to make a clear plan on how and when I will move from expert interviews to practical examples, prototyping, testing, and iteration. Given the timeframe of our thesis, having a structured roadmap will help me stay on track and make the most of the time I have left. This feedback was a great reminder that while research is essential, it needs to be paired with practical application.

Second Round: Expanding My Perspective

Thursday’s meeting with Mr. Horst Hörtner from Ars Electronica Futurelab provided a completely different perspective. We talked about my passion for universal design, which has been a key motivation behind my thesis. He introduced me to companies that develop products for the medical field and have successfully conducted medical trials, as well as projects designed with autistic people in mind. Beyond technical guidance, he gave me valuable pointers on how to approach expert interviews and tell the story behind my research. He encouraged me to clearly define why this field of design is important to me and how my work connects to real-world problems. This discussion gave me a lot of insights into the bigger picture of universal design, showing me new opportunities for research and development in this space. More than that, it reinforced the importance of being passionate about what I’m designing.

Third Round: Bringing Ideas to Life

Today, I had a meeting with Mr. Kaltenbrunner from the University of Art and Design in Linz, who is also a co-founder of Reactable Systems, one of the inspirations for my last year’s prototype for design and research. Our conversation revolved around tangible user interfaces and how they could be used for children with autism. He showed me several existing projects for autistic children, which immediately reignited my interest in creating an interactive school table. We talked about the best way to start working on this idea, and he suggested that my first focus should be on designing the UI for the interface, essentially starting with a digital app before thinking about how to integrate tangible interaction. One concept that stood out from our discussion was fictional design, a method that encourages focusing on the concept and complexity of interactions first, rather than getting stuck on the technological limitations. Given the limited timeframe of my thesis, this approach makes a lot of sense. Instead of trying to perfect the hardware immediately, I should develop the experience and interactions first, then later explore how to make them tangible. This conversation was incredibly valuable because it helped me redefine my next steps. Instead of jumping straight into prototyping the hardware, I will first develop the digital interface, refine the user experience, and then gradually explore physical interactions.

These three rounds of feedback helped me gain clarity on my direction. Moving forward, I now have a clear structure for my thesis work:

Inclusive Educational Practices for Children with Autism in Bosnia and Herzegovina

For this impulse, I focused on researching the current state of inclusive education for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Bosnia and Herzegovina. While inclusive education is officially recognized, its implementation remains inconsistent, leaving many children with autism without the necessary support to succeed in mainstream schools.

One of the key issues is that resources for individualized learning and inclusivity are limited. Schools often lack proper educational materials, adapted textbooks, and tools that could help children with ASD engage with lessons effectively. The system tends to follow standardized approaches that do not take into account the individual learning needs of children on the spectrum.

To gain deeper insight into these challenges, I conducted an expert interview with a school psychologist and a defectologist in Bijeljina. Their school is the only one in the city that offers a special education class for children with disabilities. Other schools do not have specialized support, meaning that many children with autism attend this one school, regardless of whether it is the best fit for their needs.

The psychologist explained the process of assessing students for special education. If a teacher notices that a child is struggling, they work with the school psychologist to recommend an assessment. However, it is ultimately up to the parents whether their child will be tested. In cases of ASD, students have two options: they can either join the special education class or remain in a mainstream classroom while following a curriculum for “Mild Intellectual Disability” with the support of a teaching assistant.

A major issue with this system is that the curriculum for mild intellectual disability is standardized—it is the same for all students, regardless of their individual abilities. The psychologist emphasized that children with autism require an individualized approach, yet the system does not allow for much flexibility. “The learning programs are copied from standard education systems and are not adapted to local resources and actual needs,” which often leads to frustration for students, teachers, and parents.

One of the biggest gaps in the education system is the lack of adapted learning materials. Children with ASD in special education classes do not have textbooks designed for their learning needs. Instead, teachers rely on basic tools like paper, pens, and didactic toys, which are often geared toward younger children. This creates a problem for older students, who are left using materials that do not match their cognitive level. Subjects like geography, chemistry, and physics require visual and practical aids, yet these are rarely available in special education settings.

Another significant issue is that support for children with ASD decreases as they get older. The ministry of education in Republika Srpska does not automatically provide teaching assistants for high school students. This means that families must hire private assistants if they want their child to continue education beyond primary school. The few students who continue their education often have to travel to specialized schools in Serbia, as Bosnia and Herzegovina does not offer many options nearby, beyond elementary school.

Beyond structural issues, cultural stigma surrounding autism remains a major obstacle. The psychologist and defectologist I interviewed recalled many cases where parents refused to accept that their child required special education. In rural areas, this is even more common, as acknowledging a child’s disability often means transferring them to a school in a different city, which many families are reluctant to do.

The stigma associated with autism extends beyond school. Many individuals with ASD struggle to become independent because they are not given the same opportunities to develop life skills. There are no vocational training programs tailored for individuals with autism, and work integration programs are rarely accessible to them. As a result, many children with ASD remain dependent on family care well into adulthood.

Reading and analyzing this topic helped me think critically about how educational tools could bridge some of these gaps. One key takeaway is that children with ASD need more structured and sensory-friendly learning environments—yet most schools in Bosnia and Herzegovina do not offer sensory integration tools. This directly relates to my research on designing multi-sensory learning tools that can support children with autism in adapting to traditional education settings.

Another point that stood out is the need for visual and interactive learning materials. Since children with ASD often struggle with traditional textbook-based learning, digital and physical tools could be an effective way to make subjects like geography and chemistry more accessible. I found it especially important that older children with ASD lack appropriate learning materials—a gap that my work could help address.

This research reinforced my belief that inclusive education is not just about placing children with autism in mainstream schools—it’s about making real adaptations to ensure they succeed. Bosnia and Herzegovina has taken some steps toward inclusion, but there are still significant barriers preventing children with ASD from getting the education they deserve.

For me, this is not just about identifying challenges—it’s about finding practical solutions. Designing educational tools means creating resources that make learning more engaging, structured, and supportive for children with autism. If we want to create real change, we need to rethink how we design learning environments so that they work for everyone.

Over the past few days, I’ve had some really insightful coaching sessions and discussions. While not all of them were directly related to my master’s thesis, they still provided valuable input and inspiration. I had the chance to speak with Birgit Bachler, Horst Hörtner, and Martin Kaltenbrunner, each offering a unique perspective that helped shape my thinking and approach.

Conversation with Birgit Bachler

I reached out to Birgit to ask if she would be willing to supervise my master’s thesis. We’ve had classes with her since the second semester, and I really enjoyed them. Through those courses, I realized that she’s deeply engaged in sustainable and regenerative design, which aligns well with my thesis topic. Besides that, I appreciate her approach and personality, which made me feel comfortable approaching her. Our discussion was really encouraging. She gave me useful feedback on my initial ideas, shared some valuable resources and references, and even introduced me to some of her personal projects, which we discussed in relation to my own work. She also recommended checking out „The Critical Engineering Working Group“, which I’d also suggest to anyone interested in this field. Another key takeaway from our conversation was about the scope of my thesis. I had initially assumed it would need to be much broader, but Birgit reassured me that it could be more focused. Overall, it was a great talk that left me feeling more confident about my direction.

Discussion with Horst Hörtner

My conversation with Horst was particularly thought-provoking. While it wasn’t solely focused on my thesis, we discussed my portfolio and future career prospects. He shared insights on interactive art installations and reassured me that there are plenty of opportunities in this field. That was really motivating and reinforced my idea of creating an interactive and educational installation. Beyond that, he gave me advice on breaking into the industry and recommended some studios, including „Studio Brückner“. This mention was especially eye-opening for me because it brought things full circle, I actually had classes with Uwe Brückner during my bachelor’s! I even remember him encouraging us to reach out for internships and opportunities, so this felt like an interesting connection I should explore further.

Talk with Martin Kaltenbrunner

My discussion with Martin Kaltenbrunner focused on tangible interaction and digital sustainability, both of which are key aspects of my research. His expertise provided me with a fresh perspective on how to make my project more impactful. He challenged some of my initial assumptions and encouraged me to consider alternative approaches. One of the most important insights he shared was that I don’t necessarily need to focus on just one aspect of digital sustainability. Instead, I could develop several smaller workpieces, each addressing different aspects of the topic, which I’m now seriously considering! This conversation gave me a lot to think about, and I’m excited to explore these ideas further.

Final Thoughts

Overall, these coaching sessions have been incredibly valuable. Each conversation contributed something unique, whether it was guidance on my thesis, new perspectives on my field, or a deeper understanding of key topics. I’m really grateful for the time and expertise that Birgit, Horst, and Martin shared with me. Their insights have given me fresh motivation and clarity as I move forward.

The Critical Engineering Working Group: https://criticalengineering.org/

Studio Brückner: https://studio-uwe-brueckner.com/

Julian Oliver: https://julianoliver.com/

For my last Impulse, I want to talk about the feedbacks I gather from 3 different experts. This week I had to chance to talk about my thesis expose with Ursula Lagger, Mr. Horst Hörtner from Ars Electronica Futurelab, and Mr. Kaltenbrunner from the University of Art and Design in Linz.

Ms. Lagger focused on my methods and the clarity of my exposé. She advised me to decide whether interviews are necessary and to refine my research focus. Her feedback reminded me of the importance of making my approach as clear as possible.

Mr. Hörtner gave me advice on presenting my work. After showing him my projects and portfolio, he suggested highlighting only three main projects that I want to pursue in the future. This helped me think about how to present my research in a more structured and impactful way.

Mr. Kaltenbrunner provided useful resources for my research and emphasized the importance of planning my installation. He suggested creating a draft, either in 3D or as a sketch, to clarify my concept. Since I already have experience with conceptual design, he encouraged me to refine my idea before moving into the production phase.

From these discussions, I learned that having a clear and focused exposé is crucial for my thesis. I also realized the importance of structuring my future projects and visually planning my installation before execution. These insights will help me stay organized and make my work more effective.

This feedback helped me see my next steps more clearly. Now, I will refine my thesis exposé, and start planning my thesis installation in a more structured way. Now, I feel more confident about how to move forward. These conversations really showed me the importance of balancing research with practical application!

Talking to experts in your field can be intimidating. You go in expecting deep, philosophical discussions, maybe some critique, and — if you’re lucky — a few words of encouragement. Over the last two days, I had the chance to speak with two experts in human-computer interaction: Horst Hörtner from Ars Electronica Futurelab and Mr. Kaltenbrunner from the University of Art and Design in Linz. These conversations were part of my university schedule, but what I got out of them was much more than just academic feedback.

One conversation felt like a motivational boost (with a healthy dose of honesty), while the other was more of a crash course in rethinking my approach to my master’s thesis. Both were interesting, challenging, and, at times, unintentionally hilarious.

—

Horst Hörtner: Put Some Ego Into It!

First up was Horst Hörtner, a leading expert in human-computer interaction and the managing director of Ars Electronica Futurelab — an institution at the cutting edge of digital media, design, art, and technology. So, you know, no pressure.

From the moment we started talking, it was clear that Horst is not one to sugarcoat things. He gave me some incredibly encouraging feedback about my work, calling it kinda impressive — which, coming from someone at Ars Electronica, felt like getting a thumbs-up from the tech gods. But then he followed up with something unexpected:

“You should definitely put more ego into talking about your work.”

I had to laugh because, honestly, he’s not wrong. I’ve always believed in my work, but I tend to present it in a more straightforward, no-big-deal way. Horst, however, made it clear that confidence is not just about knowing you’re good — it’s about making sure everyone else knows it too. He said I already sound confident (as I should, apparently, because I’m “very good” at what I do — his words, not mine! 😆), but I need to own it even more.

Then came the part that didn’t surprise me at all.

“Everything I see here shows me that you’re a workaholic.”

Guilty as charged. I don’t even know how to argue with that one. But it’s nice when someone at one of the most important digital media institutions in Austria recognizes my dedication — workaholism and all.

—

Mr. Kaltenbrunner: A Masterclass in Master’s-Thesis Thinking

Next, I had my conversation with Mr. Kaltenbrunner, professor at the Institute of Media Studies in Linz, head of the Tangible Music Lab, and co-inventor of the Reactivision framework. Basically, a serious expert in my field. This talk, though… this was an experience.

I had roughly five minutes to present my master’s thesis topic, then in between the few rare moments I was allowed to answer his questions, I got some very insightful feedback.

Here are the key takeaways from our conversation:

1. Collaboration is key.

– One of his biggest concerns was that my prototype shouldn’t feel like I just send my grandpa a link and then never check in again (Which, to be fair, would be kind of rude, but if you take a few seconds to listen to me, you would know that would never be the case for me and my prototype.)

– The app needs to focus on genuine collaboration — a space where family members actively contribute rather than just passively consuming information.

– This made me rethink how to design interactions that actually bring families together, rather than just giving them access to shared content.

2. Storytelling, Legacies, and Family Heirlooms.

– He suggested I go deeper into the storytelling aspect — not just digital legacies but also physical heirlooms (letters, objects, photos). And I know this one as it makes total sense because, honestly, what’s family history without the things we pass down? Whether it’s an old watch, a recipe book, or that one piece of furniture nobody wants to get rid of, heirlooms hold as much history as the people who owned them.

– It made me realize that my app prototype could include ways to document objects and their stories, turning them into digital keepsakes.

3. Version 1.0 is Enough (For Now).

– Mr. Kaltenbrunner reminded me that my master’s thesis doesn’t have to be the final, polished version of my project. It can be a solid Version 1.0, and I can build on it later.

– This was honestly a relief to hear. As someone who tends to go all-in on projects (see: *workaholic*), I sometimes forget that progress is better than perfection.

4. Make an Explainer Video.

– He suggested that I create a short promotional video to explain my prototype — something that could be shared on social media and clearly demonstrate the app’s purpose.

– This was actually an amazing idea. Not only does it help communicate my project visually and concisely, but it’s also a practical way to generate interest and potential future collaborations.

—

What These Talks Mean for My Future Work and Design

Both of these conversations reinforced some important lessons about confidence, design, and the creative process:

– Confidence matters. If I’m good at what I do (and, apparently, I am), I need to talk about my work with pride and conviction.

– Collaboration should be at the heart of my project. The prototype isn’t just a digital archive — it’s a space for families to interact, share, and co-create their history.

– Objects tell stories too. My prototype should allow users to document not just people, but the heirlooms and artifacts that carry family history.

– Version 1.0 is enough. My thesis is just the beginning, and I can continue refining and expanding my project long after I submit it.

– Explaining ideas visually is crucial. A well-crafted video can make an abstract concept tangible, which is a skill I’ll definitely need in future projects.

—

Final Thoughts: Two Days, Two Experts, Tons of Inspiration

Talking to Horst Hörtner and Mr. Kaltenbrunner gave me exactly what I needed — encouragement, constructive critique, and fresh ideas to push my thesis forward.

Horst reminded me to own my skills and talk about my work with more confidence (and also called me out for being a workaholic, which… fair). Mr. Kaltenbrunner, on the other hand, helped refine my thesis direction, giving me a clearer vision of how to make my prototype more collaborative and meaningful.

After these conversations, I feel more motivated, focused, and — dare I say it — ready to embrace my inner workaholic to bring this project to life.

And who knows? Maybe next time, I’ll talk about my work with a *little* more ego. After all, if you’re good at something, why not let everybody know? 😏

As I look back on the final week of my studies at the FH, I had the chance to engage in several feedback sessions that have proven to be incredibly insightful in shaping the direction of my Master Thesis. These discussions have given me a clearer understanding of how to proceed with my research. While the feedback varied, it has helped me refine my focus and define the next steps for my thesis, allowing me to consider several potential directions.

The first round of feedback centered on my Exposé, and the main takeaway was that my topic needed further narrowing. Although I had already considered focusing the topic, hearing this point helped me realize the importance of it again. My research idea is initially quite broad, and the feedback highlighted that by refining my focus, I could dive deeper into the subject matter and avoid becoming overwhelmed by its scope. This feedback has been essential in helping me move from a general concept to something more precise, but I know there is still work to be done to define it even further.

On Thursday, I had a discussion with an external expert who helped me gain a better understanding of the significance of my thesis in the broader design field. The expert highlighted that the topic is intriguing and important, especially in the context of adaptive interfaces and awareness control – and that there is still much to explore, particularly in the design domain. The expert also suggested focusing on a single system where adaptive changes would be valuable, rather than trying to address multiple systems with uncertain demand. One of the most helpful insights was the emphasis on perception psychology and the way external factors, such as lighting and user attention, influence how an environment is perceived. These insights reinforced the idea that I should aim to create adaptive interfaces that respond to specific contextual factors, such as lighting conditions or the user’s level of awareness. By narrowing the focus to one such system, I would be able to provide more meaningful insights. It became clear that the next step should be to dive into awareness control studies and related research, to better understand how one adaptive interface could be implemented in various contexts.

In my meeting with my thesis supervisor, the advice was to start with a broader focus and then refine it as I gathered more data. This approach seemed very practical, as it allowed me to work in a more flexible way, without feeling pressured to make a final decision right away. Instead of committing to a single example immediately, I was encouraged to start working in the area and refine my focus as I moved forward. This felt liberating, as it gives me the opportunity to explore the general topic before narrowing it down based on my findings. My supervisor also suggested focusing on one practical use case later one, such as maps or mobility systems for example – an area I had already considered but hadn’t fully committed to yet. Given that adaptive design could add significant value in these systems, I began to realize that this could be a potential direction to explore. However, I also decided that this focus is not yet fixed, and I have the flexibility to decide later on whether I want to pursue mobility systems or something else entirely.

As I continued to reflect on the feedback, another external expert reminded me of the importance of context when designing adaptive interfaces. This expert emphasized that different contexts – such as different environments or use cases – have a huge impact on how interfaces should adapt. For instance, navigation systems for bicycles need to account for lighting conditions and external factors like weather or speed, which wouldn’t be as critical in other contexts, such as car navigation systems. This feedback underscored the importance of considering real-world scenarios and environmental factors when developing adaptive prototypes. By simulating these conditions, I could better understand how adaptive interfaces perform and how users interact with them

Given all the feedback I’ve received, I have decided that the next step is to begin with deeper research into adaptive interfaces and awareness control. I will start by exploring existing research and looking into studies across various fields, including design, technology, psychology, and sociology. This will provide me with a better understanding of where the gaps in research lie and help me refine my focus. While I have already gathered substantial feedback about the potential of mobility systems and maps as an application for my thesis, I’m still undecided on whether this is the direction I want to take. The feedback has given me many solid entry points into this area, but I need to carefully consider whether this focus aligns with my interests and the goals of my thesis. There’s still the possibility that I might decide to explore another area entirely. If I choose to go in a different direction, I can still apply the same feedback to other systems and contexts. The decision will be made once I continue my research and start exploring practical examples and case studies. By reviewing papers and understanding the different challenges in the design of adaptive interfaces, I will be able to determine if mobility systems and maps are indeed the right focus, or if another domain would offer more opportunities for meaningful exploration.

In conclusion, this final week of feedback sessions has been crucial in helping me define the next steps for my Master Thesis. While mobility systems and maps are strong potential directions, I’m still open to exploring other areas. My immediate next step is to begin deepening my research into adaptive interfaces and awareness control, and based on this research, I will make an informed decision on whether to pursue mobility systems or another area. With a clear plan for starting my research and refining my focus as I go, I am excited to move forward and see where my thesis journey leads.

Am 20. Januar 2025 besuchte ich ein klassisches Konzert im Congress Center Graz. Die Veranstaltung wurde von den renommierten Wiener Symphonikern unter der Leitung von Patrick Hahn gespielt, mit Kian Soltani als Solisten. Das Programm war sorgfältig kuratiert und kombinierte klassische Meisterwerke mit ausdrucksstarken Interpretationen. Die Akustik des Saals bot ein immersives Hörerlebnis und brachte die feinen Nuancen der Orchesterdarbietung zur Geltung.

Bereits beim Betreten des Konzertsaals fiel mir auf, dass das Publikum hauptsächlich aus älteren, wohlhabend wirkenden Menschen bestand. Die Atmosphäre wirkte elitär, was mich als Neuling in der Welt der klassischen Musik etwas unsicher machte. Ich fragte mich, ob ich hier überhaupt richtig war. Ein Konzert dieser Art hatte ich zuvor noch nie besucht, und obwohl ich offen für Neues war, fühlte ich mich in diesem Umfeld zunächst etwas fehl am Platz.

Die Körperhaltung der Musiker war unerwartet wild, was eine besondere Dynamik in das Konzert brachte. Gleichzeitig fühlte ich mich als Außenstehende – ich wusste nicht einmal genau, was eine Symphonie ist. Das Orchester spielte mit beeindruckender Präzision, die Synchronität der Musiker:innen war faszinierend. Es wurde schnell deutlich, wie viel Disziplin und Übung in solch einer Performance stecken muss. Besonders Patrick Hahn dirigierte mit solch einer Energie, dass es fast wie ein Tanz-Workout wirkte.

Die Sitzplatzgestaltung im Saal stellte sich als problematisch heraus. Die grünen Kinosessel waren so ausgerichtet, dass ich mir durch das ständige Drehen zur Bühne meinen Nacken verrenkte. Nach der ersten Hälfte bekam ich Kopfschmerzen. Eine Drehung der Sitze um 30° Richtung Bühne wäre eine echte Verbesserung.

Die Zielgruppe des Konzerts war mir nicht sofort klar. In den Pausen und nach dem Konzert wirkten viele Besucher:innen unsicher, ob es weitergeht oder ob die Veranstaltung zu Ende ist. Es herrschten gedämpfte, fast erzwungene Gespräche, was mich noch fehlplatzierter fühlen ließ. Besonders auffällig war, dass einige Gäste in der zweiten Hälfte (zumindest in den ersten Reihen) ihre Plätze tauschten – ein Phänomen, das mir zunächst rätselhaft erschien.

Beim Verlassen des Saals wurde ich mehrfach unhöflich angerempelt – es fühlte sich an, als ob wohlhabendere Konzertbesucher:innen sich einfach mehr herausnehmen könnten. Draußen gab es nur wenige Tische, die bereits vor Konzertbeginn von besonders schnellen Besucher:innen erobert wurden. Diese Dynamik überraschte mich und ließ mich darüber nachdenken, wie viel unausgesprochene Regeln es in solchen Umfeldern gibt.

Besonders hilfreich fand ich die lauten Kommentare einiger Gäste, die mir Orientierung gaben. Es gab ein ungeschriebenes Regelwerk: Ein einzelner Gong bedeutete „Es geht los!“, mehrere Gongs signalisierten ein noch dringlicheres „Jetzt aber wirklich rein!“. Musiker hörten auf zu spielen, das Publikum klatschte – oder eben nicht. Ich fragte mich, woher alle wussten, wann das Klatschen angebracht war. Der Mann hinter mir kommentierte: „Ah, Pause! Gehen wir uns die Beine vertreten.“ Diese Hinweise halfen mir, das Konzert besser zu verstehen und gaben mir Sicherheit.

Trotz meines anfänglichen Gefühls des Fremdseins konnte ich viel aus dem Konzert mitnehmen. Es war beeindruckend zu sehen, mit welcher Hingabe die Musiker:innen spielten und wie sehr sie in ihrer Kunst aufgingen. Das Konzert zeigte mir, dass Musik eine universelle Sprache ist, auch wenn sie für mich als Zuhörerin zunächst fremd erschien.

Allerdings wurde mir auch bewusst, dass klassische Konzerte mit einer gewissen Exklusivität behaftet sind. Die Atmosphäre wirkte distanziert, und es gab viele unausgesprochene Verhaltensregeln, die für Außenstehende nicht sofort verständlich waren. Die Sitzplatzgestaltung, die Unsicherheiten in den Pausen und das Verhalten des Publikums deuten darauf hin, dass es Verbesserungsmöglichkeiten in der Gestaltung des Konzerterlebnisses gibt, um es inklusiver und zugänglicher zu machen.

Dieses Konzert lieferte mir wertvolle Erkenntnisse für meine Masterarbeit zur Optimierung der Prozesse im Musikverein Graz. Besonders die Besucherführung und deren Unsicherheiten bieten interessante Ansatzpunkte. Beispielsweise könnten verständlichere Hinweise für Pausen und das Konzertende das Erlebnis verbessern. Auch die Gestaltung der Sitzordnung und der allgemeinen Besucherführung wäre ein Bereich mit Potenzial.

Ein weiterer relevanter Aspekt ist die Barrierefreiheit – nicht nur physisch, sondern auch in Bezug auf die Verständlichkeit der Abläufe. Viele Menschen könnten sich durch die Atmosphäre eines klassischen Konzerts abgeschreckt fühlen. Durch eine benutzerzentrierte Gestaltung von Hinweisen, eine interaktive Einführung oder eine optimierte Kommunikation könnten solche Veranstaltungen einem breiteren Publikum zugänglich gemacht werden.

Die emotionale Verbindung, die durch die Performance geschaffen wurde, verdeutlicht außerdem die Bedeutung einer durchdachten Veranstaltungsplanung im Kulturbereich. Mein persönliches Erlebnis unterstreicht die Relevanz von Usability und User Experience auch in nicht-digitalen Räumen wie Konzertsälen. Diese Erkenntnisse werde ich in meine weitere Forschung einfließen lassen und analysieren, wie klassische Musikveranstaltungen zugänglicher gestaltet werden können.

Some ideas never lose relevance, no matter how much time passes. The three TED Talks I reviewed — Taryn Simon’s The Stories Behind the Bloodlines, Andrew Solomon’s Love, No Matter What, and Jeffrey Kluger’s The Sibling Bond — all explore themes of family, identity, and the ways our relationships shape us. Even though these talks were given over a decade ago, their messages feel just as urgent today, especially in the context of my master’s thesis and the genealogy app prototype I am developing.

Each of these talks, in its own way, challenges how we think about lineage, love, and human connection. They don’t just focus on where we come from — they explore what family means, how we define it, and how we preserve those relationships over time. These themes are deeply relevant not only for my thesis but also for designing better tools that bring people together, both in digital and physical spaces.

—

Taryn Simon: The Stories Behind the Bloodlines

Taryn Simon’s talk takes a fascinating approach to genealogy — not as a simple record of who begat whom, but as a collision of order and chaos. She traveled the world documenting bloodlines and their complicated, often painful histories. Some families were torn apart by corruption, genocide, or war, while others carried legacies of political power, migration, or survival — and this hit close to home, because not too long ago all of this happened in my home country too. Her project, A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters, exposes how bureaucracy, history, and fate shape family narratives, sometimes erasing people altogether.

One of the most haunting stories she tells is about a man in India who was declared legally dead because his relatives bribed officials to take over his land. On paper, he does not exist. And yet, here he is — a living contradiction. This highlights a deeper truth: our official records do not always reflect our lived realities.

Why this matters for my thesis and my prototype:

– Many genealogy tools focus on official documentation, like birth certificates and census records. But what happens when those records are missing, manipulated, or just wrong?

– My prototype should allow users to tell their family stories in a way that goes beyond bureaucracy — through photos, voice recordings, and personal memories.

– The way Simon presents her research — structured bloodlines clashing with fragmented footnotes — reminds me once again that genealogy isn’t just about names and dates; it’s about the tension between order and disorder, memory and erasure.

—

Andrew Solomon: Love, No Matter What

Andrew Solomon’s talk is about identity, acceptance, and the complexity of family love. He explores the idea that some identities — like race or nationality — are passed down through generations (vertical identities), while others — like being deaf, gay, or neurodivergent — do not match what parents expect (horizontal identities). Families often struggle with these differences, sometimes rejecting their own children because they do not fit traditional molds.

Solomon tells heartbreaking and hopeful stories of parents learning to accept children they once feared they would never understand — parents of children with Down Syndrome, disabilities, or even children who became violent. One mother, whose son was a perpetrator of the Columbine massacre, wrestles with the painful reality of loving a child who caused immense harm. Solomon’s point is clear: love and acceptance are choices, not automatic responses.

Why this matters for my thesis and my app prototype:

– Genealogy is often treated as a linear inheritance, but real families are far more complicated. A family tree does not always reflect the relationships that truly shape us.

– My prototype should maybe allow users to define family beyond biology — including adopted family members, close friends, or mentors who have played essential roles in shaping their lives.

– Solomon’s discussion of acceptance and difference is relevant to design itself. Good design is inclusive — it acknowledges that not everyone fits into a neat category. Whether designing for accessibility or creating a platform that allows for non-traditional family structures — these ideas could shape my work, but I’ll cross that bridge when I come to it.

—

Jeffrey Kluger: The Sibling Bond

Jeffrey Kluger’s talk is a love letter to sibling relationships — the longest and often most formative relationships in our lives. He argues that siblings shape us in ways parents never can, influencing our personalities, our social skills, and even our career paths. Unlike parents, who eventually leave us, and children, who come into our lives later, siblings walk the entire journey with us (hopefully).

Kluger also dives into birth order psychology, explaining how firstborns tend to be more responsible and achievement-oriented, while younger siblings develop charm and humor as survival mechanisms. He talks about favoritism in families, the impact of competition, and the deep, often unspoken loyalty between siblings — even when they drive each other crazy. And as someone who has a much older brother, I can say that I agree with most of things said, but of course, every relationship is different.

Why this matters for my thesis and my app prototype:

– Sibling relationships are often overlooked in genealogy research. Most apps focus on parent-child connections, but my app could include features that highlight the influence of siblings — shared experiences, childhood memories, and inside jokes. That is why I’m putting so much emphasis on storytelling.

– Kluger’s insights on birth order could inspire new ways to visualize family history. Imagine an interactive feature where users could see how birth order shaped different generations in their family.

– More broadly, his talk reinforces that family history is not just about tracing ancestors — it’s about understanding the relationships that made us who we are and I’m all here for it.

—

Why These Talks Matter for Design and My Future Work

All three talks remind me that family is not just about genetics — it’s about stories, connections, and human experiences. This is directly relevant not only for my master’s thesis but also for the future of interactive design, digital storytelling, and genealogy apps.

1. Storytelling is just as important as data.

– Genealogy tools should not just be family trees with facts — they should help people tell their family’s stories in rich and interactive ways. Taryn Simon’s approach to visually documenting bloodlines reminds me that history is not always clean and structured. My prototype should reflect both the order and the messiness of family history.

2. Relationships shape us more than we realize.

– Kluger’s discussion on sibling influence reminds me that genealogy apps should capture family dynamics, not just names. Whether designing genealogy tools, interactive exhibitions, or user-centered platforms, I want to focus on how people relate to one another — not just how they are related.

—

Conclusion

These TED Talks reaffirm something I already believed: family history is not just about looking backward — it’s about understanding who we are today. Taryn Simon reveals how official records don’t always tell the full story, Andrew Solomon reminds us that family love is sometimes a journey, not an instant fact, and Jeffrey Kluger proves that our siblings shape us more than we think.

For my thesis, for my app prototype, and for my future as a designer, these lessons will stay with me. Whether I’m working on genealogy, interactive storytelling, or user experience, the goal is the same: to create spaces where people can connect, reflect, and preserve the stories that truly matter.

Ein paar Tage nach dem ersten Gespräch mit Herrn Baumann habe ich mich mit ihm, Dr. Michael Nemeth und Mag. Livia Krisch, BA im Musikverein getroffen. Gemeinsam haben wir besprochen, was die Anliegen sind und wohin eine Kooperation und eine Thesis möglicherweise laufen könnten.

Nachdem sich alle vorgestellt hatten, habe ich ihnen präsentiert, was ich in meiner Thesis gerne alles inhaltlich abdecken würde und sie haben mir Themen vorgestellt, bei denen sie Bedarf hätten, bzw. bei denen ich sie unterstützen könnte.

Schnell haben wir einen gemeinsamen Nenner gefunden, uns grob auf einen Themenbereich geeinigt und einen Termin ausgemacht für ein weiteres Treffen, bei dem ich Interviews mit allen möglichen Mitarbeiter:innen führen, mich im Verein umsehen und Fragen stellen dürfte. Dieses sollte direkt nach den Weihnachtsfeiertagen stattfinden.

Zudem wollen sie meine Thesis in einem Newsletter ausschicken, um mich so mit weiteren Interviewpartnern (Mitgliedern des Musikvereins) zusammenzuführen.

Außerdem wurde besprochen, dass es wohl sinnvoll wäre, wenn ich zusätzlich dazu auch mit anderen, externen Personen über das Thema sprechen würde, da eines der Ziele, die sie gerne erreichen würden ist, dass sie mehr Mitglieder gewinnen möchten, bzw. neue/ mehr Besucher in die Konzerte bringen wollen.

Das Gespräch ging gerade einmal eine halbe Stunde, dennoch haben wir alle Rahmenbedingungen, sowie das weitere Vorgehen grob besrpochen. Alle Beteiligten gingen mit einem guten Gefühl aus der Besprechung und wissen, wie es weitergehen soll.

Das Thema für meine Thesis wurde genauer definiert und festgelegt. Zudem habe ich mit Herrn Baumann besprochen, dass er mein Betreuer für die Thesis werden soll.