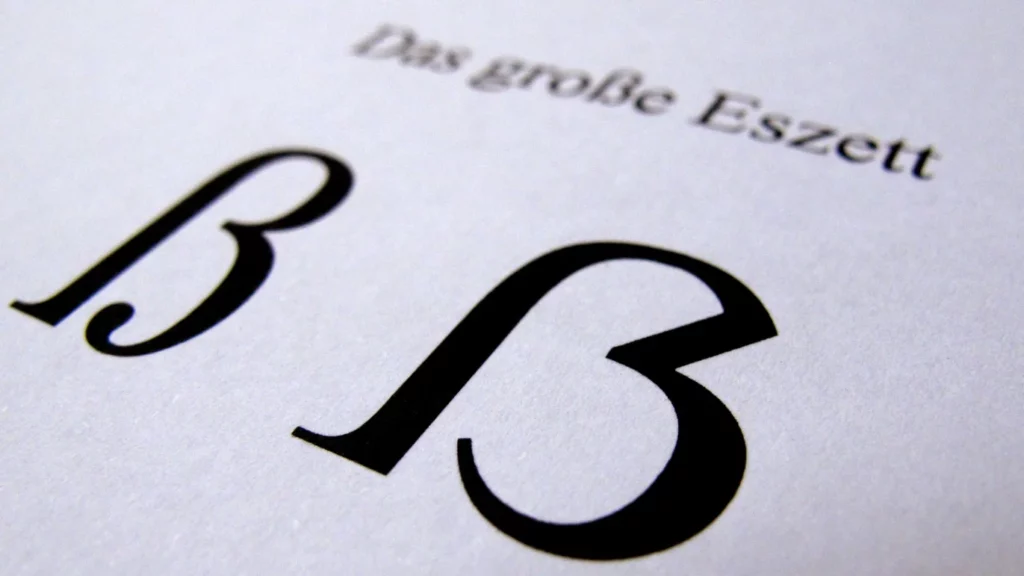

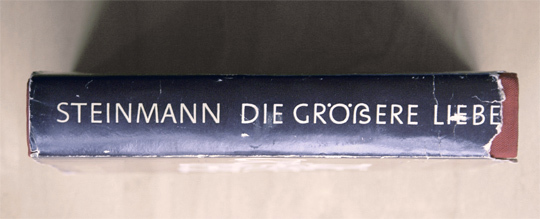

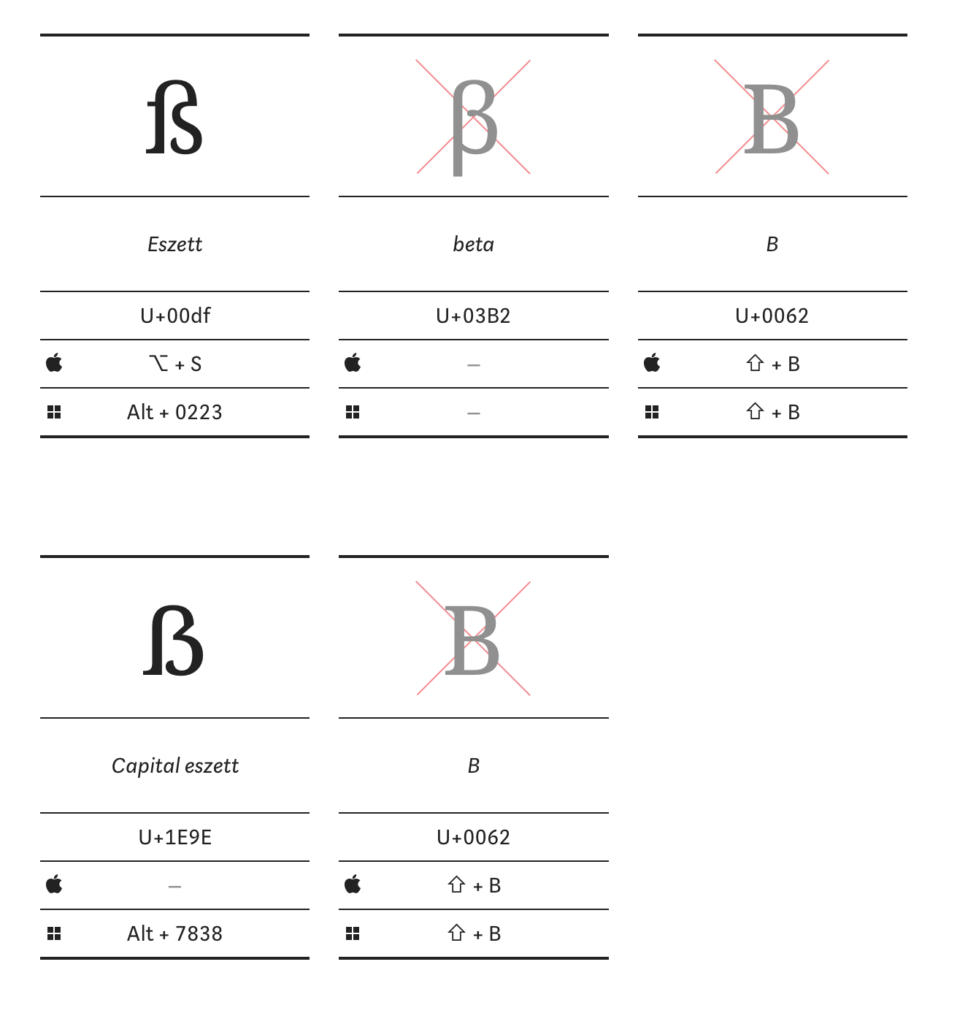

The Eszett, both in lowercase (ß) and uppercase (ẞ), is often confused with the Greek letter Beta (β), particularly in uppercase where it resembles the letter B. The uppercase Eszett is also frequently mistaken for the letter B.

This potential for confusion arises due to the visual similarities between these characters, especially in certain fonts or when they are not clearly displayed. In scientific and academic contexts, where precision is of utmost importance, the differentiation between these characters becomes crucial to avoid misunderstandings and inaccuracies.

It‘s important to note that the Eszett has specific orthographic rules in the German language, while the Greek Beta and the English letter B have different linguistic contexts and applications.

German letter B

This visual similarity can lead to confusion for non-German readers who may not be familiar with the Eszett. The association of the Eszett with the German letter B is sometimes humorously referred to as „German B,“ as it can resemble the English B at first glance.

This confusion is further exacerbated by the different stylistic variations of the Eszett in various fonts. Some font designers may not be acquainted with the specific orthographic rules of the Eszett or may consciously opt for a creative variation. This results in a range of appearances, with some versions closely resembling the letter B. The mix-up between the Eszett (ß) and the German B is rooted in visual similarities and specific stylistic choices in fonts.

Greek letter „β“ (beta)

In scientific writings, precision plays a crucial role, especially when utilizing non-English letters. It is important to carefully distinguish the German letter „ß“ from the Greek letter „β.“ While „ß“ is specific to the German alphabet, „β“ is frequently employed in biomedical research and mathematics.

The risk of misunderstandings arises because both letters look similar but represent different linguistic contexts. „ß“ is used in the German language and follows specific orthographic rules, whereas „β“ is utilized in Greek and disciplines such as biomedical research and mathematics.

A specific issue arises when authors mistakenly use „ß“ for „β“ or vice versa. This can lead to confusion in scientific literature. Authors have the right to request corrections from scientific journals in case of inaccurate representation of their names or other terms.

Overall, this underscores the importance of precise usage of letters and characters in scientific works to avoid errors and misunderstandings, ensuring the quality of scientific communication.

Links

https://typefacts.com/en/blog/the-german-capital-letter-eszett

https://identum.at/de/2018/08/21/das-scharfe-s-vong-morphologie-und-history-her