Introduction

In the realm of digital storytelling, few experiences are as intricate and immersive as „Cyclops,“ an alternative reality game crafted by artist Trevor Paglen. „Cyclops“ serves as a masterclass in nonlinear, interactive narrative, demanding a blend of diverse knowledge areas from its players. This makes it an ideal case study for my authoring tool, which is designed to enable the creation of complex, multifaceted stories that engage audiences in unique and profound ways. Through this blog post, I want to explore how „Cyclops“, with its sophisticated storytelling structure, perfectly aligns with the capabilities of a robust authoring tool.

Summary

„Cyclops“ is an intricate and intimidating alternative reality game designed by artist Trevor Paglen. It features a basic black-and-white digital interface reminiscent of 1970s computer systems and demands extensive knowledge in fields like cryptography, vintage computers, logic, music, and PSYOPS history. Launched at the 2023 Chaos Communication Congress, it required 700 professional hackers three days to reach just the fourth level. Since then, a dedicated group on Discord has continued to collaborate, achieving 53% completion of level three. The game immerses players in complex puzzles and psychological challenges, often guided by Eliza, a reference to the first chatbot, enhancing the sense of psychological warfare.

Paglen’s goal was to create a public art project native to the online world, fostering a community united by shared interests in digital security and coded messages. Cyclops prompts players to reflect on their relationship with digital media and social interactions, blurring the lines between gaming and psychological manipulation. Paglen and his team of experts spent a year developing this intricate digital landscape, which echoes the haunting possibility that today’s internet might be an extension of historical psychological control programs like MK Ultra.

My Conclusions

The main reasons why “Cyclops” is a suited as a case study for my project are:

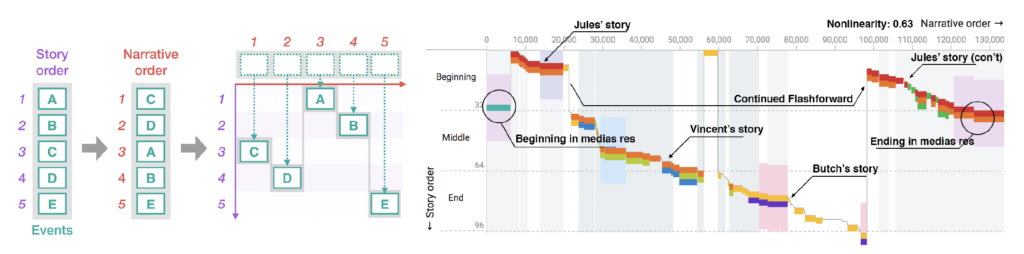

- Its Complex Narrative Structure: „Cyclops“ features a nonlinear storyline that challenges players to navigate through cryptographic puzzles, vintage computer systems, and psychological tests. This complexity requires an authoring tool that can handle multiple narrative branches and interconnected storylines seamlessly.

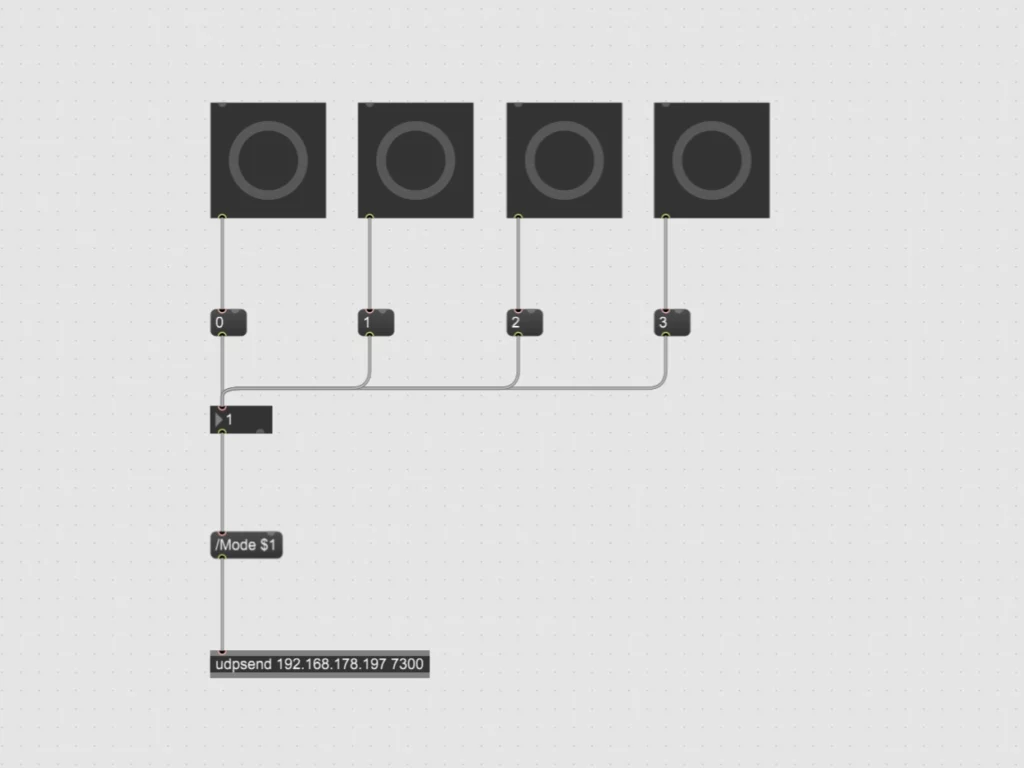

- Interactive and Immersive Elements: The game’s integration of various media forms, such as audio tracks, ASCII scripts, and visual puzzles, demonstrates the need for an authoring tool capable of embedding diverse interactive elements that enhance user engagement.

- Collaborative Problem-Solving: „Cyclops“ necessitates collective intelligence and collaboration, which can be facilitated by an authoring tool that supports multi-user interaction and real-time collaboration features. This feature would go outside of the pure realm of an authoring tool for storytellers but could be an interesting future feature to give the player of any ARG a platform where they are able to collaborate, solve and piece together the story that the artist is trying to convey.

References

https://donotresearch.substack.com/p/artist-profile-trevor-paglens-cyclops