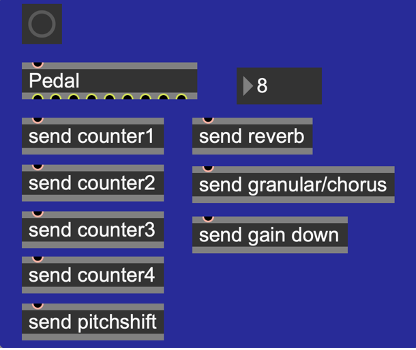

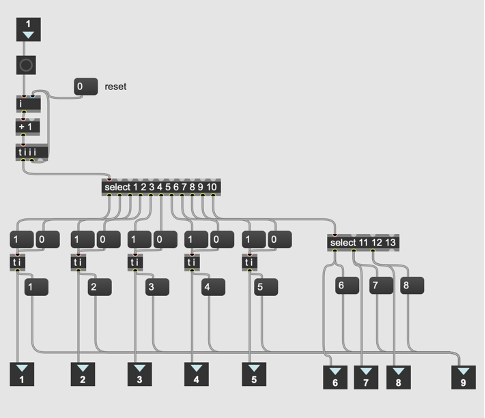

The piece is based on both the played and recorded materials. While it holds an overall concept, it is not a traditional written score but rather, it depends heavily on and is closely connected to the processed sounds and the programming aspect. The core idea of the piece revolves around the transition from the acoustic sound of the violin to processed and electronic sounds. This transition reflects with my own musical journey, from a classical violinist to an electroacoustic musician. Although the piece is not fully improvised, it still allows for a sense of freedom, enabling the performer to interact with the processed sounds, which vary each time during the performance. The structure of the piece is sectional, and with each step, it shifts further into the electronic domain. The starting point of that is a loop of each buffer, where the sounds are heard not being played in real-time by the performer.

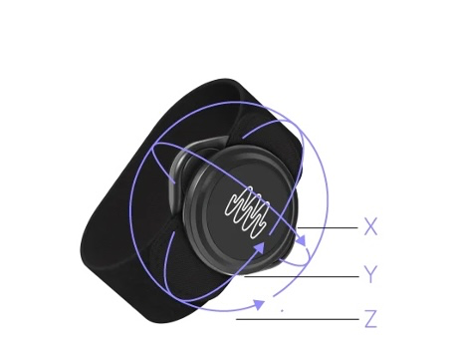

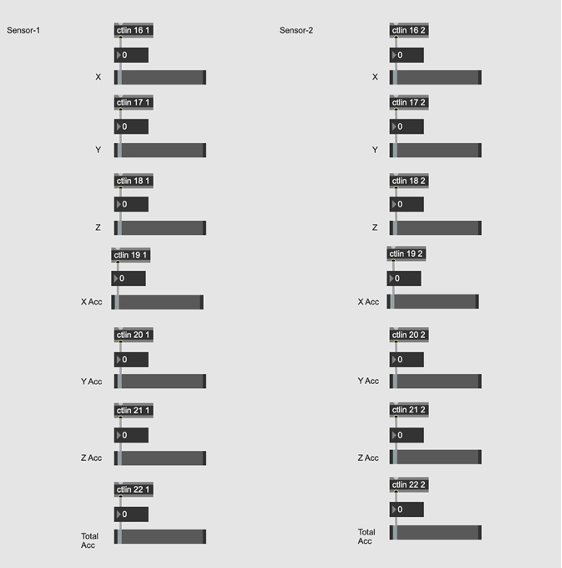

Pieces like Suspensions by Atau Tanaka[1] and Weapon of Choice by Alexander Schubert[2] and also the book of Marije Baalman Composing Interactions[3], played a significant role in shaping the artistic direction of this set up. They helped me establish a connection between the technical and artistic aspects of the it, and to blend improvisation with electronic manipulation in a meaningful way.

My intention was to unify the entire piece, where in addition to the processed sound, the performer also plays live. This way, the piece does not entirely become electronic, instead it creates a polyphonic sound where different materials blend into each other. I also aimed to incorporate extended techniques on the violin, such as bowing on the body of the instrument, to capture the texture of the wood’s sound, among others. These techniques create variations with each performance attempt.

Since there is no fixed score for the piece, the timing is inherently variable. It depends not only on the recorded materials but also on the length and nature of the interactions between the performer and the electronic sounds. The performer’s engagement with the processed sounds can fluctuate, leading to different pacing and moments of intensity. Although that there is more or less clear that the most intense or the chaotic part is the moment that granular patches arise.

Towards the end of the piece I considered two possible approaches, both of which could be easily implemented within the patch. The first scenario involved abruptly cutting off the sound while the piece remained in its chaotic phase, with the violin accompanying this sudden act. The second scenario entailed first progressively increasing in intensity and then gradually fading out, so this version has a more gradual transition. These two variations could significantly alter the conceptual framework of the piece as well, either aligning with my intention to conclude with a sense of resolution or opening the door to further exploration and discovery. For now, I have chosen to conclude the piece by gradually reducing its dynamic intensity and stabilizing the sound. However this decision is not necessarily final, as the compositional process remains open to further refinement.