In this blog entry I will explore the use of chaos in graphic design and look at projects that incorporate chaos as a central theme in the design process. I will delve into the stories behind the disorder that shapes modern design, from strategic visual identity design to the current trend of chaotic maximalism.

Navigating Chaos – Creating Visual Identity by Using Chaos Theory

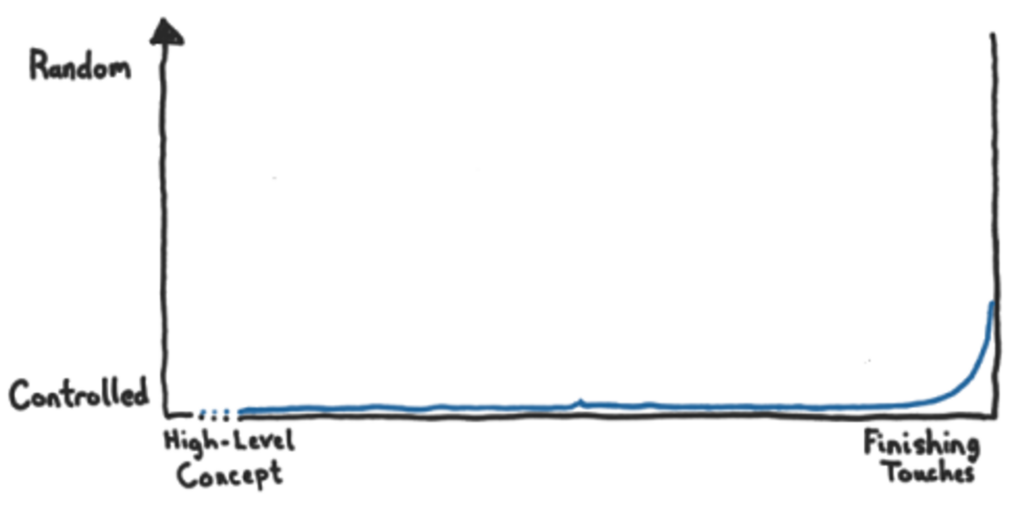

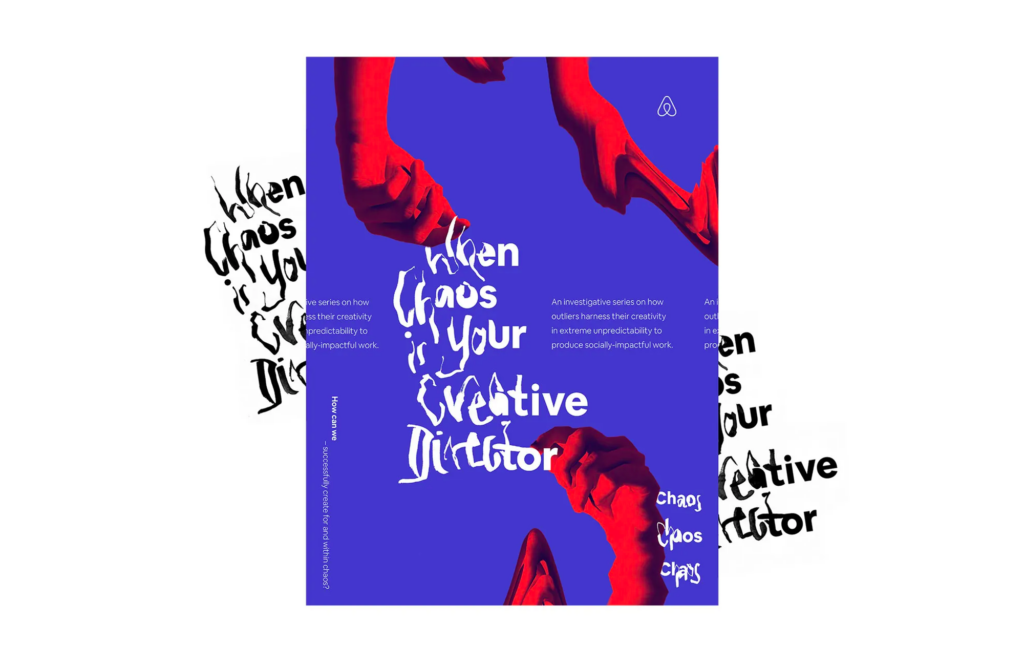

In the journey to create the visual identity for the second season of Airbnb Design Talks, chaos took center stage, challenging designer Meredith Schomburg to unravel the complexities of disorder in the design process. Given the paradoxical task of designing a system around chaos, Schomburg was quickly captivated by her initial ideas. However, she soon realized the need to navigate the chaotic nature of the design process and avoid letting the allure of the initial concept overshadow the depth that comes from exploring different creative directions.

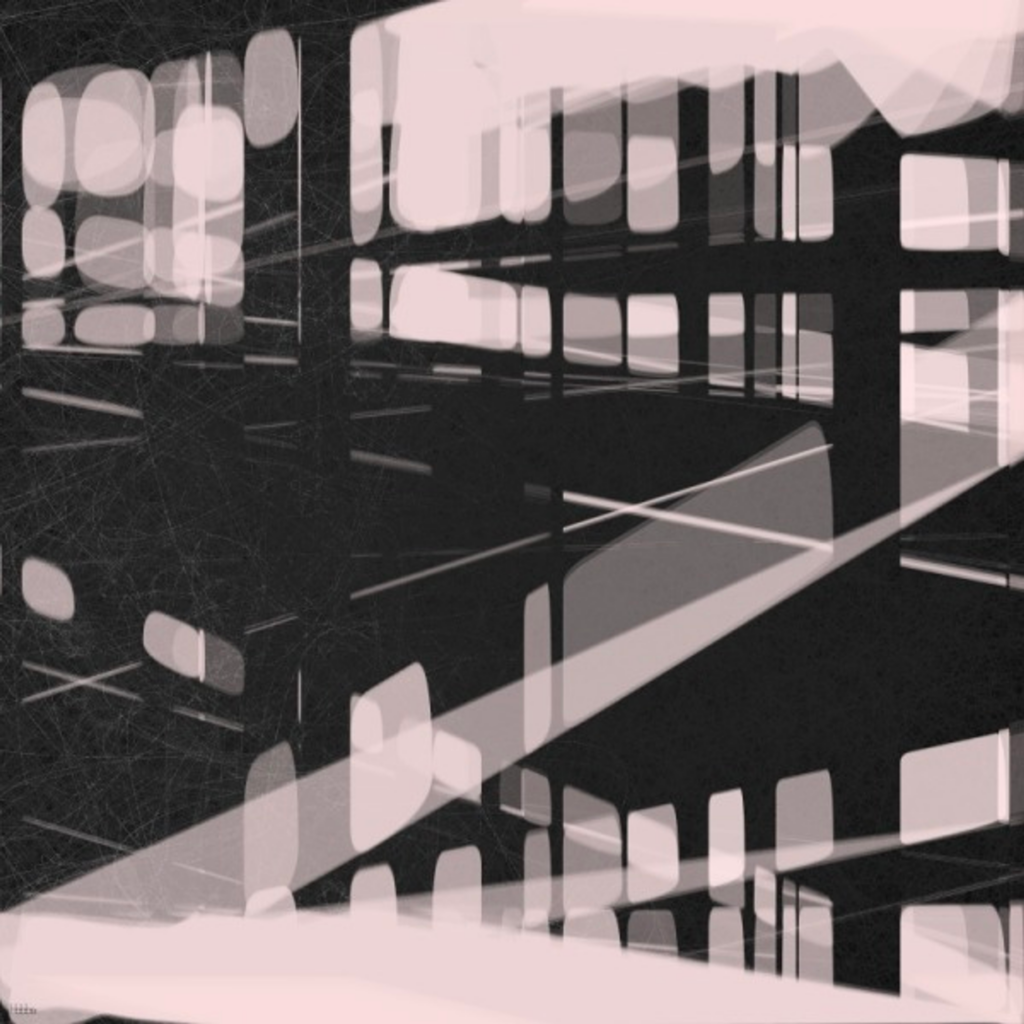

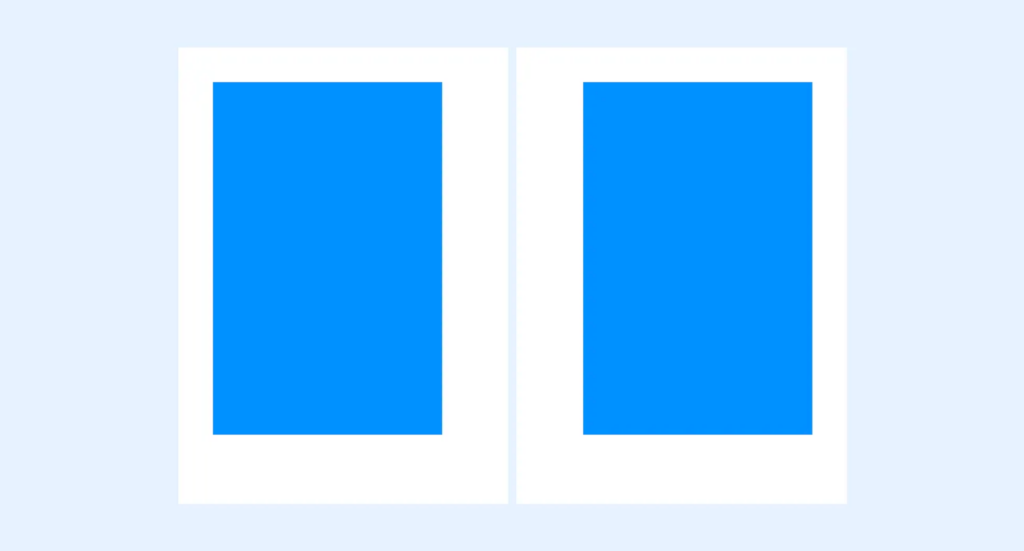

The first design attempt resulted in a visually chaotic collage. Utilizing basic Photoshop filters distorted images, and the suggested event materials displayed the speaker’s name written in nearly illegible handwriting. The aim was to generate visual chaos through the amalgamation of random elements on a page. While it showcased the theme, it lacked the inherent order that the season was meant to celebrate. Schomburg emphasizes the challenge of resisting the rush to implement the first idea, as it can limit the exploration of alternative concepts and hinder the creative process.

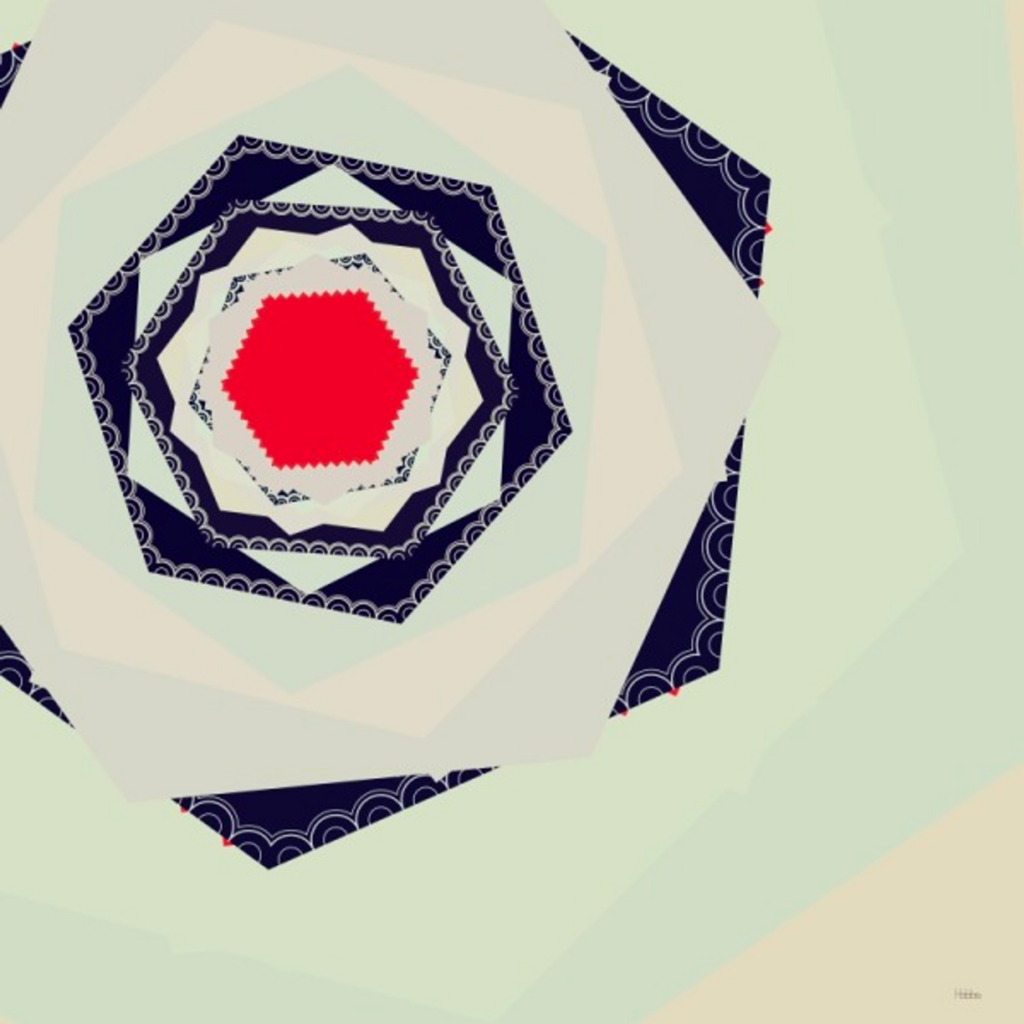

By highlighting the chaos within the design journey, Schomburg emphasizes the importance of giving meaning to the design process. She encourages intentional storytelling within the art direction, ensuring that each concept is guided by principles and defining characteristics that promote clarity and authenticity in the narratives presented. At the second attempt she designed everything to fit the story, showing that even though it seemed chaotic at first, there were hidden patterns underneath – making the refined concept more organized than the random initial direction.

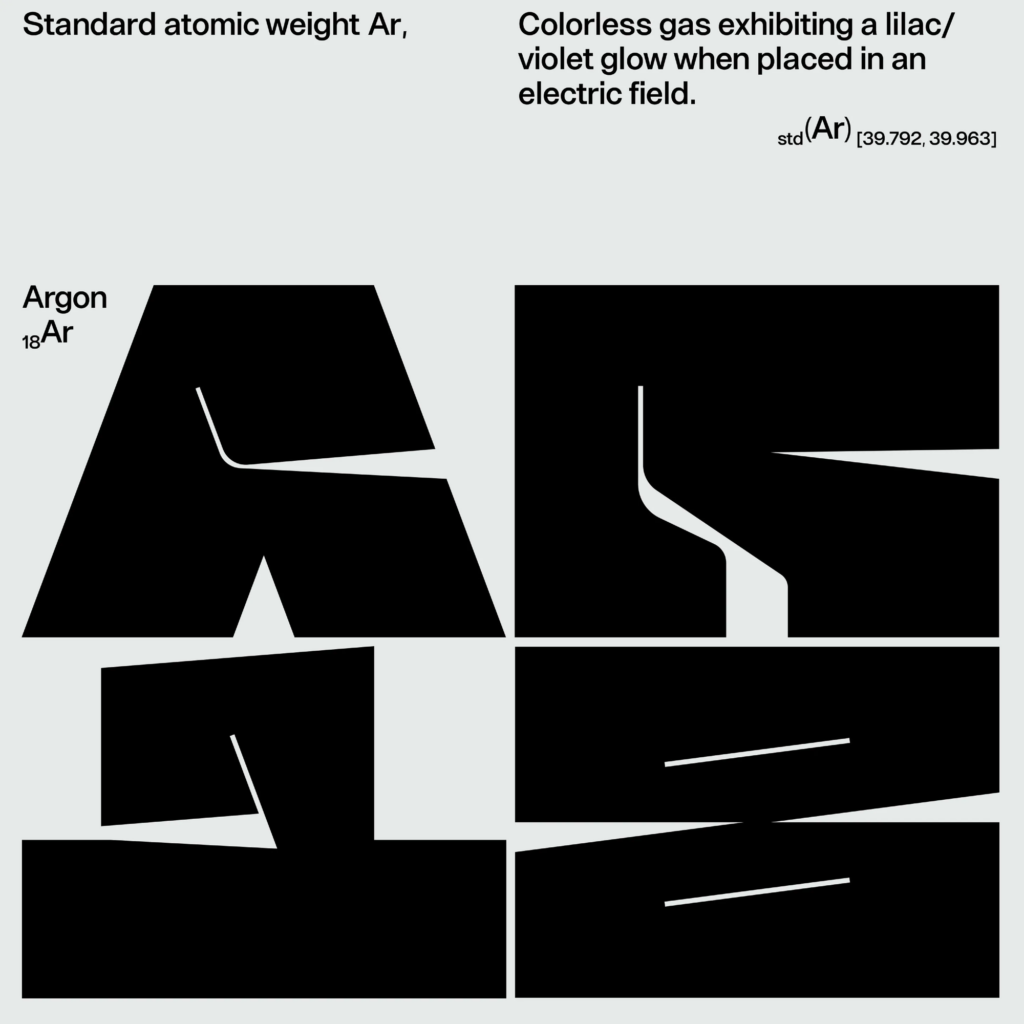

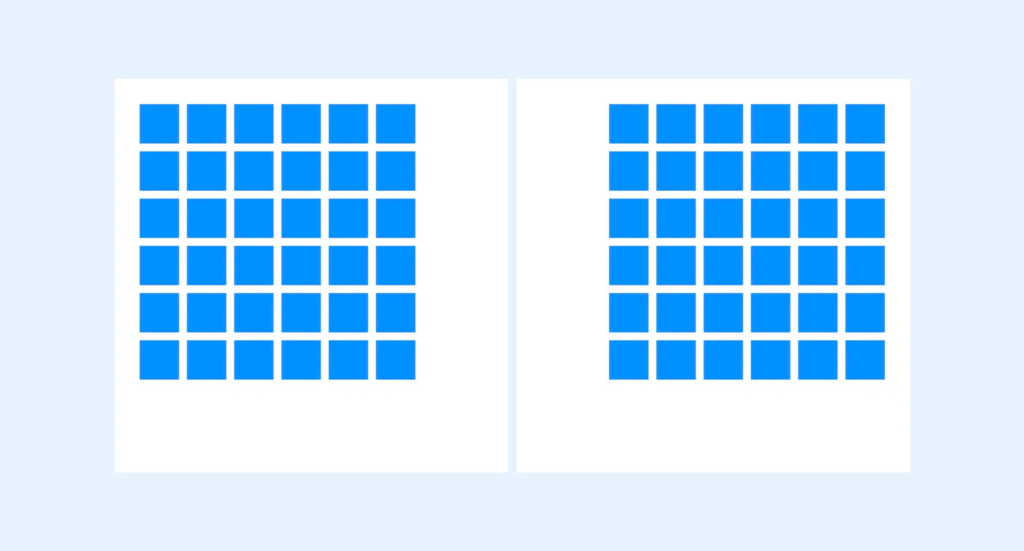

As the project evolved, the team delved into chaos theory and uncovered the presence of underlying patterns within apparent randomness. This revelation inspired a refined concept in which every design element was meticulously aligned with Chaos Theory, revealing order within perceived chaos. The color scheme was a more vibrant adaptation of Airbnb’s brand colors. Pictures, although fragmented and scattered on the page, were arranged based on a collection of geometric fractals inspired by the visual patterns of Chaos Theory in nature.

In conclusion, the case study highlights the importance of navigating the chaotic design process, slowing down to explore alternative concepts, and bringing intentional meaning to the creative journey. It encourages designers to embrace chaos, allowing for a more deliberate and purposeful approach to creating authentic and impactful visual identities.1

Chaotic Maximalism – Design Trend for Gen Z

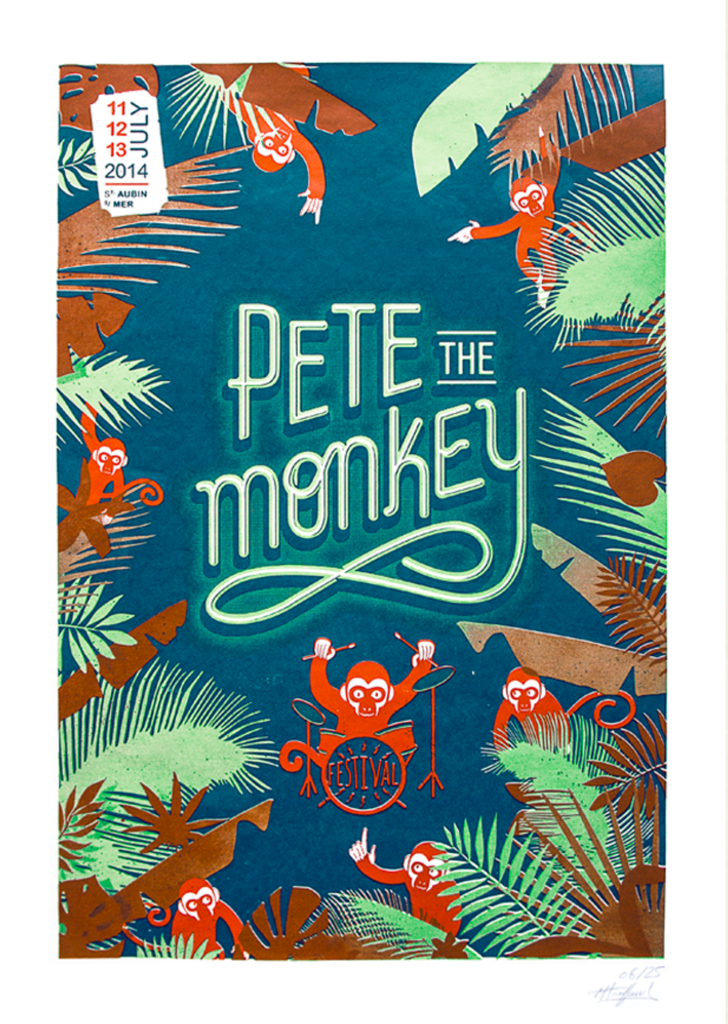

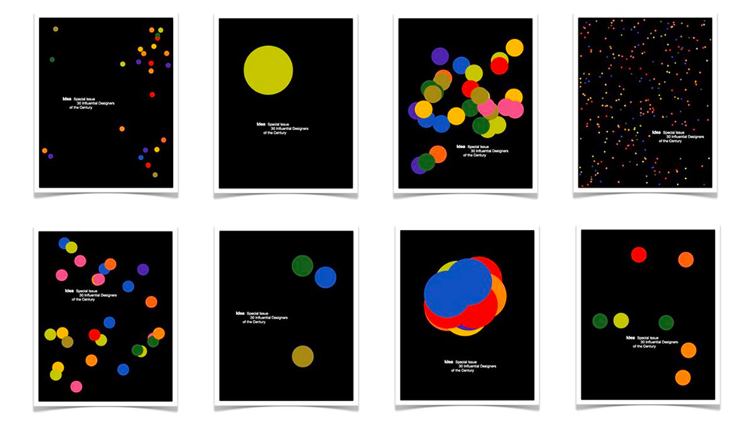

In the ever-evolving world of design trends, the concept of chaotic maximalism has emerged, challenging the traditional norms and boundaries of graphic design. Unlike the minimalist preferences of Millennials, Gen Z’s rejection of set rules has paved the way for a trend that embraces an explosion of color, pattern, and visual elements – chaotic maximalism.

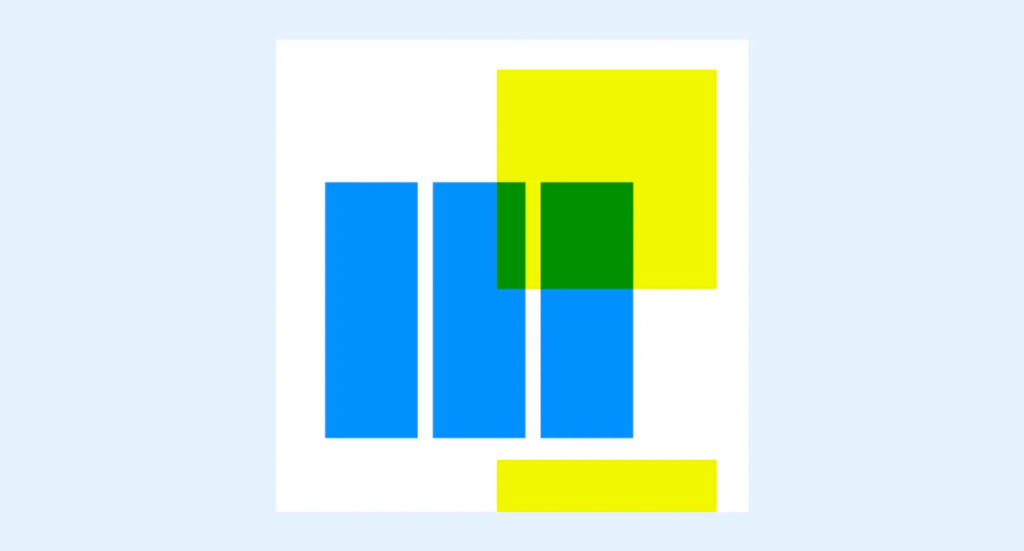

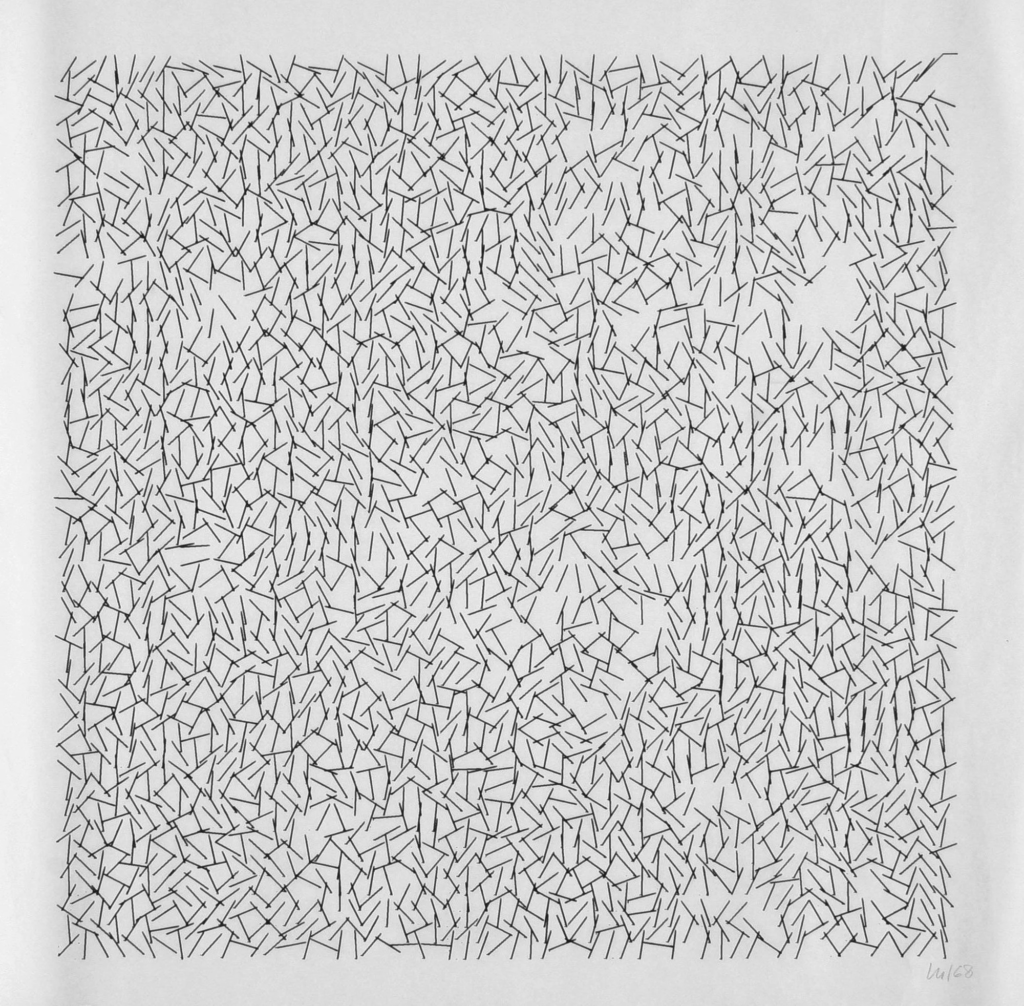

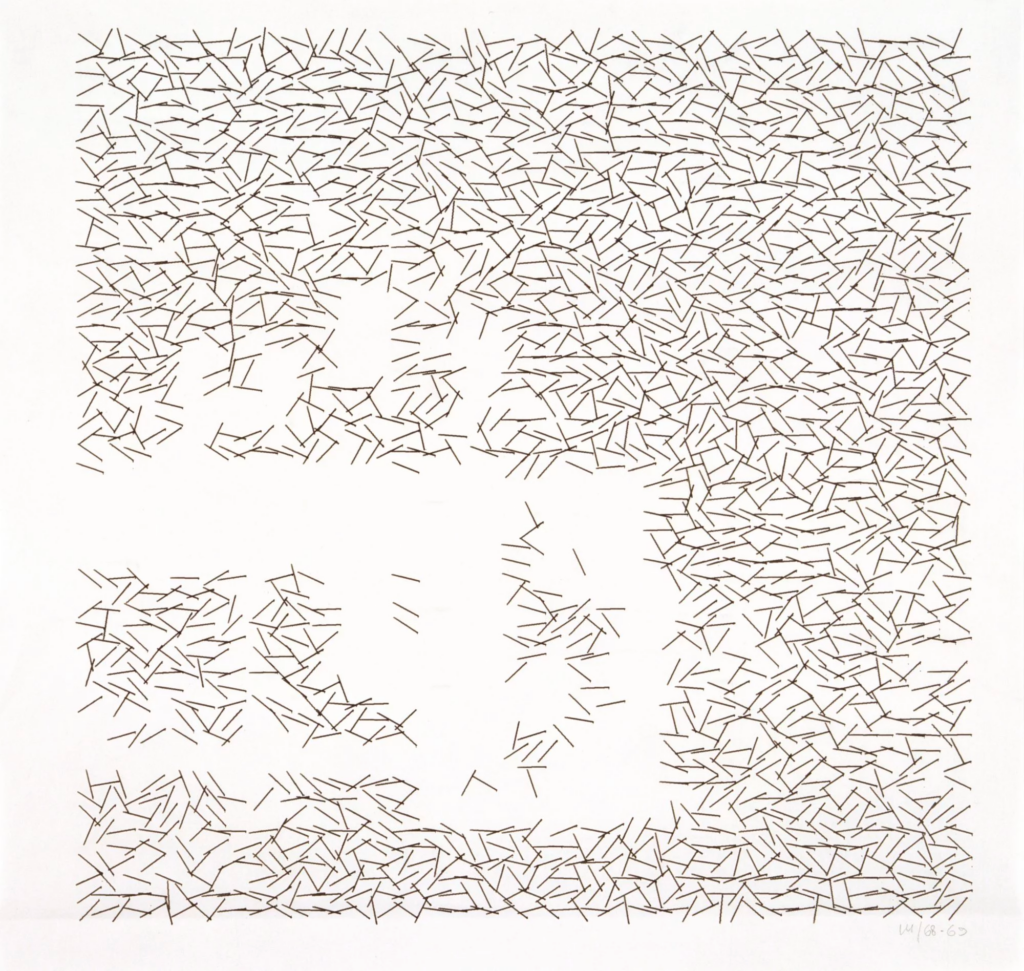

Emerging from the postmodern movement as a reaction to the rigid principles of modernism, chaotic maximalism celebrates diversity and individual expression by incorporating elements from different styles, eras, and cultures. This trend defies conventional design rules, opting for an overwhelming abundance of visual elements, including vibrant colors, playful patterns, collage, and meticulous attention to detail.

In the Chaotic Maximalism trend, designers blend diverse influences from different historical and contemporary eras, resulting in a collision of creative styles. Vibrant color schemes with clashing hues and surprising combinations attract attention, while playful patterns, collages and layering create visually dense and intricate designs.

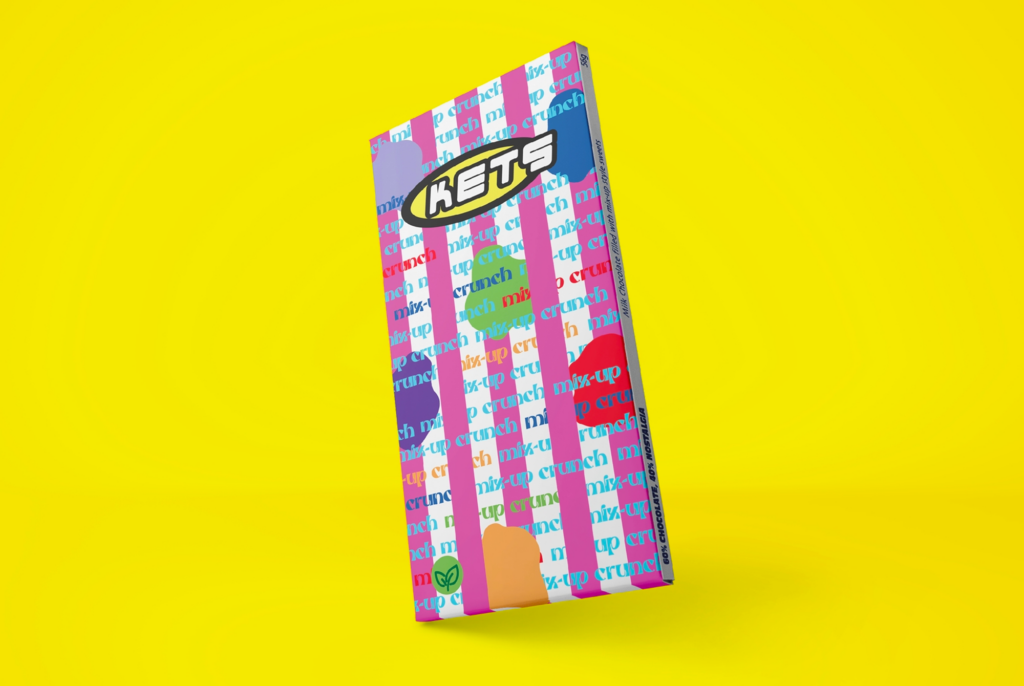

The article of JUMP Brand Communications Agency showcases the design team’s exploration of chaotic maximalism through a creative brief focused on candy packaging, presenting striking examples of their work.

Konpeitō

Inspired by Studio Ghibli, Hannah Jauneika contrasts chaotic maximalism with serene scenes, using a vibrant color palette and incorporating the star shape of konpeitō.

Mix-Up Crunch

Tapping into childhood nostalgia, Alana Whenary’s Y2K-style design integrates vibrant colors and playful elements from classic TV shows like Scooby-Doo.

Candyland

Gemma Turnbull envisions Candyland as a fantasy pick ’n‘ mix emporium, incorporating vibrant patterns inspired by traditional sweet bags.

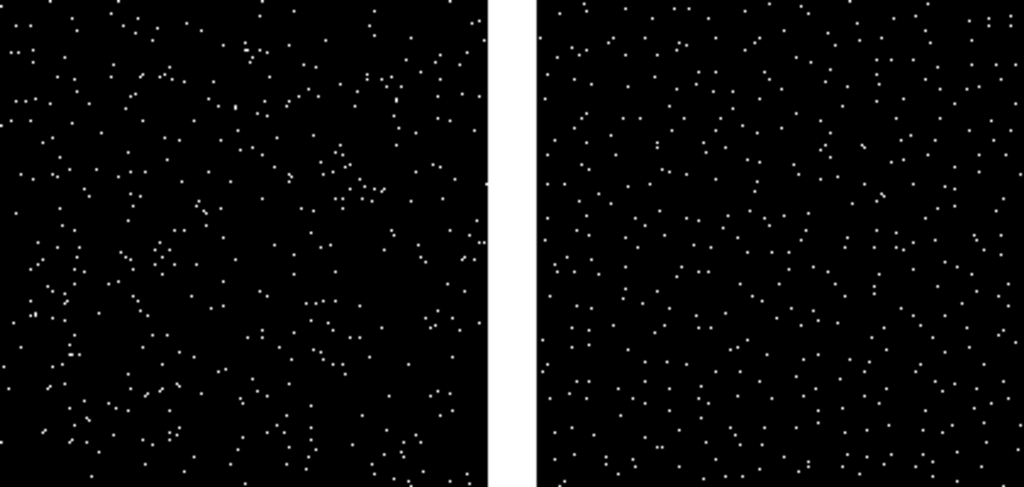

Astros

Laura Haverson’s Astros concept draws inspiration from outer space, creating a collective solar system that aligns seamlessly with chaotic maximalism. 2

Invention, it must be humbly admitted, does not consist in creating out of void, but out of chaos.

– Mary Shelley

Sources: