So far, I’ve spent most of my time on the structure of the app, which dictates what the sound needs to support, but I haven’t worked on the auditory cues yet. These cues should support first responders when they are unable to look at the phone while following instructions. As this semester is coming to an end, this will not make it into my final prototype, instead I have started a free association to extend the visual cues with auditory cues.

What is needed?

My first thoughts were three requirements: An alert-like sound to draw attention to the device, a voice that gives instructions as shown in the emergency steps, and loop functionality.

One requirement for the alarm tone is that it must be audible to everyone, everywhere, as much as possible. Some emergency situations may involve difficult sound environments, so the frequency and volume of the sound should be chosen appropriately.

The second requirement is a voice that gives instructions and supports the visual information on an auditory level. The first idea for customized emergency information about one’s specific condition was to have the voice recorded by the person with epilepsy itself. But this would increase the interaction costs, because users would have to double the information input: textual and verbal. Even if the concept would be extended to support more than one language, the effort would increase and become less feasible for people due to lack of language skills. Second, it is uncertain whether the recording quality and the way each user speaks are sufficient to be clearly understood.

For this reason, a generated voice based on text input would be more appropriate for such a concept. AI-based speech engines have gotten better over time and are able to convert text to speech with very little processing time. The technology is there and the results sound more natural and authentic than ever before. In the case of user-created emergency steps, the speech must be generated in the background after the text is entered, so that it can be played back without delay in the moment the emergency steps are opened.

The loop functionality requires infinite repetitions so that the sound does not have to be restarted manually, but it should also allow muting when not necessary or too intrusive.

Audio timeline

I also thought about when the sound should be used.

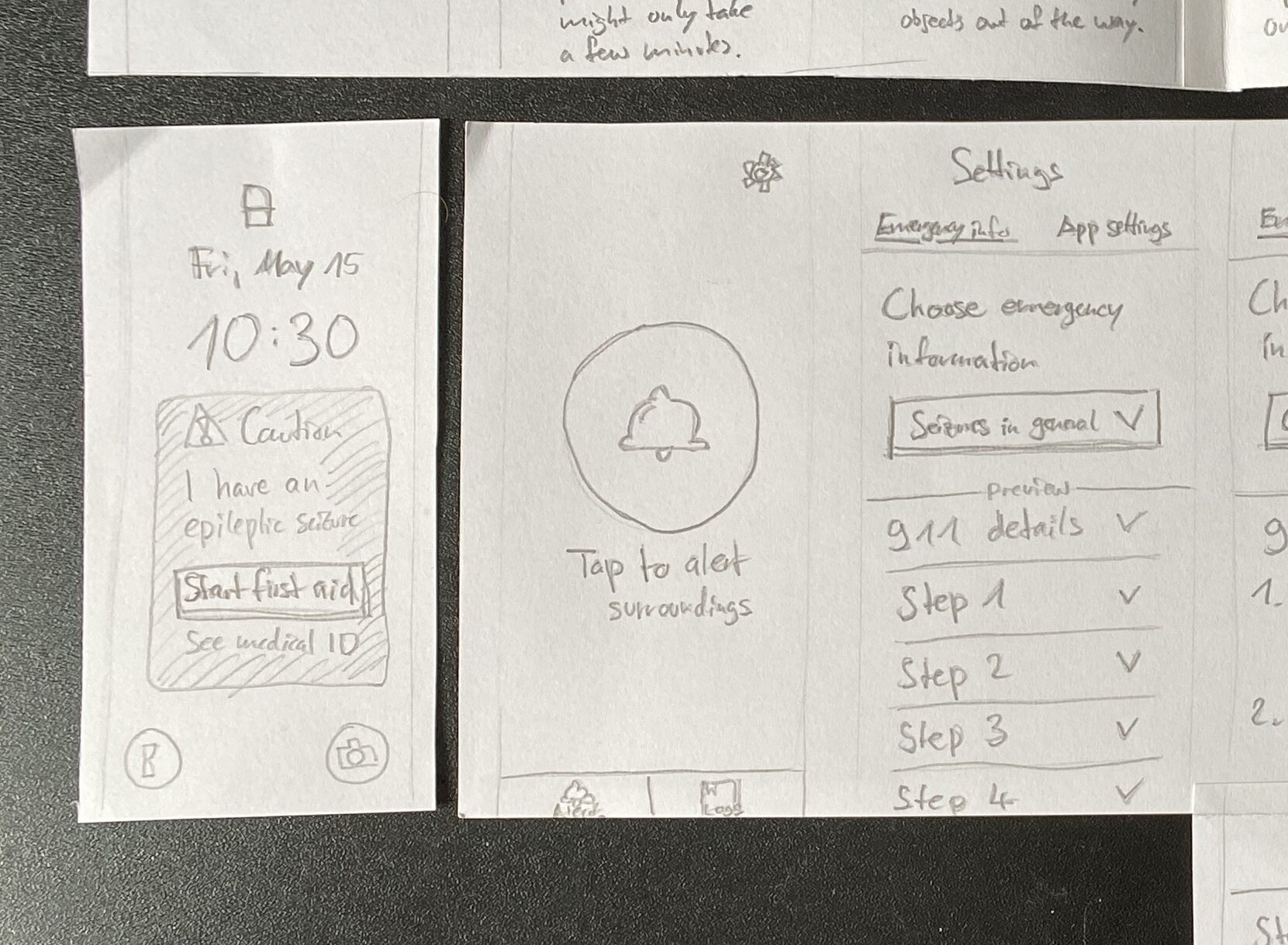

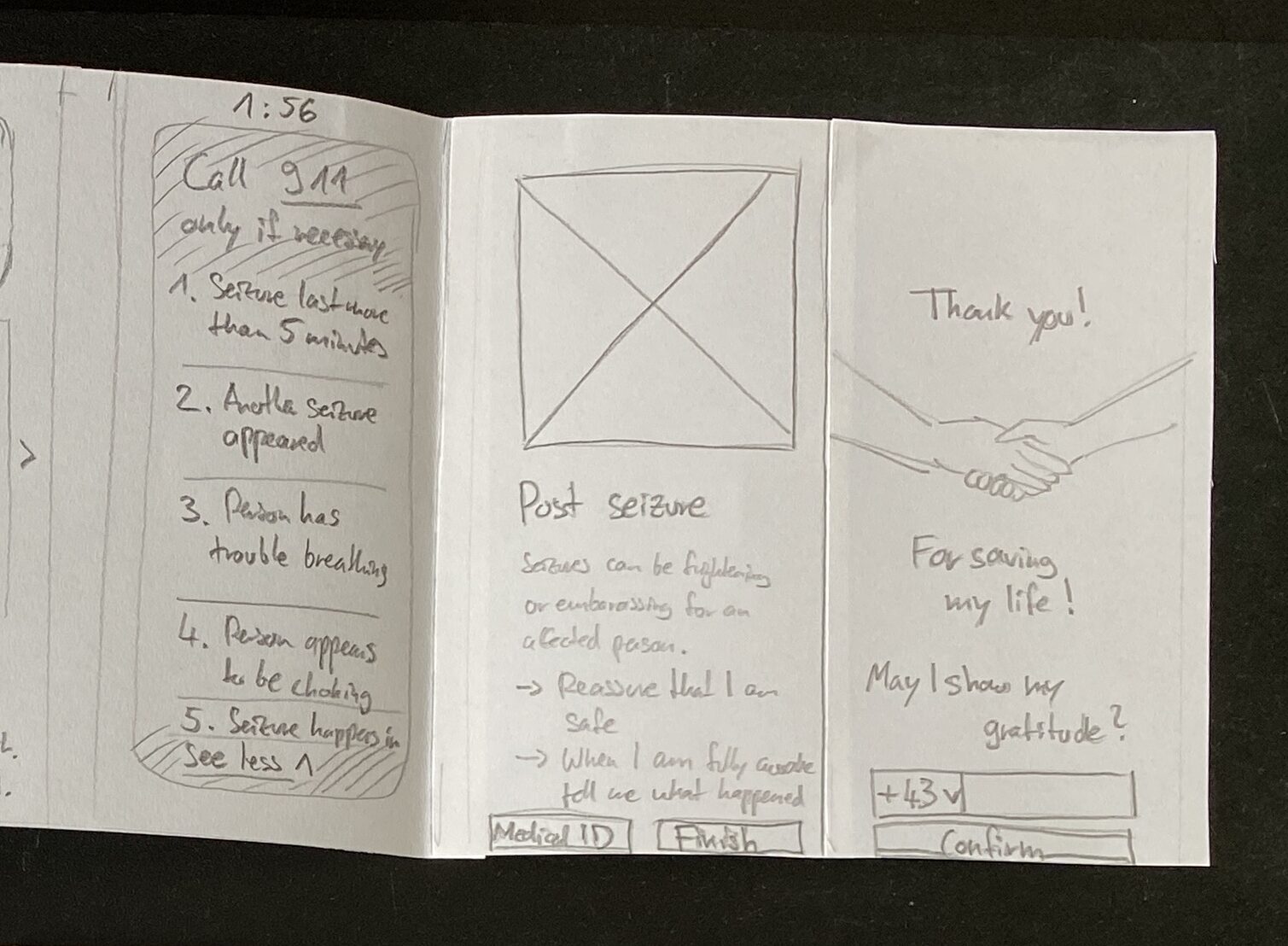

After an alarm is triggered automatically by sensors or manually by the affected person and the timer is running, the alarm sounds. This continues until a first responder initiates the emergency steps by pressing „Start first aid“.

Next, a voice reproduces what is displayed on the screen in a well-pronounced and clear way. This is played in a loop until a user swipes to see the next emergency step. In this way, each piece of information is extended aurally until the emergency steps are completed by the user.

The information on the following screens does not require further auditory cues.