On the 27th of October, a lecture performance by designer Evelyn Roth took place as part of the program of the Vienna based “re:pair festival” 2024. The lecture performance dealt with the role of the repair process in the current fashion system. Under the title “REPAIR!_Fashion – The Relevance of Repair as an Act of Creativity in Circular Processes”, Roth engaged in an act of repairing a garment live on stage before elaborating on the role and the status of the act of visibly repairing and mending garments. Using the example of a blouse, Roth illustrated the repair process as a socio-political statement and creative act. Within the design context, the lecture discussed the possible future of design processes in circular workflows.

The focus of the talk was on the emerging hierarchical change in the structure of fashion: REPAIR!_Fashion aimed to be understood in the context of a systemic and structural change in fashion. Repairing fashion provokes an expanding aesthetic perception and a political positioning that the act of repairing as a design process entails. In the words of Orsola de Castro, upcyclist, fashion designer, author and co-founder of Fashion Revolution: “Repairing your clothes can be a revolutionary act. “1

About Evelyn Roth

“Evelyne Roth is a designer and a lecturer on the BA in Fashion Design, the MA Master’s Studio ICDP and the cross-institute CoCreate programme of the FHNW Academy of Art and Design. She has held posts at a number of institutions as an expert in Design Thinking and Forecasting. Questioning common processes in the fashion industry, attempting to break with them and launching products that make a contemporary statement are all part of her holistic brief as a designer. Her practice and teaching in design focus on circular design, research, conception and materiality.”2

Key Takeaways

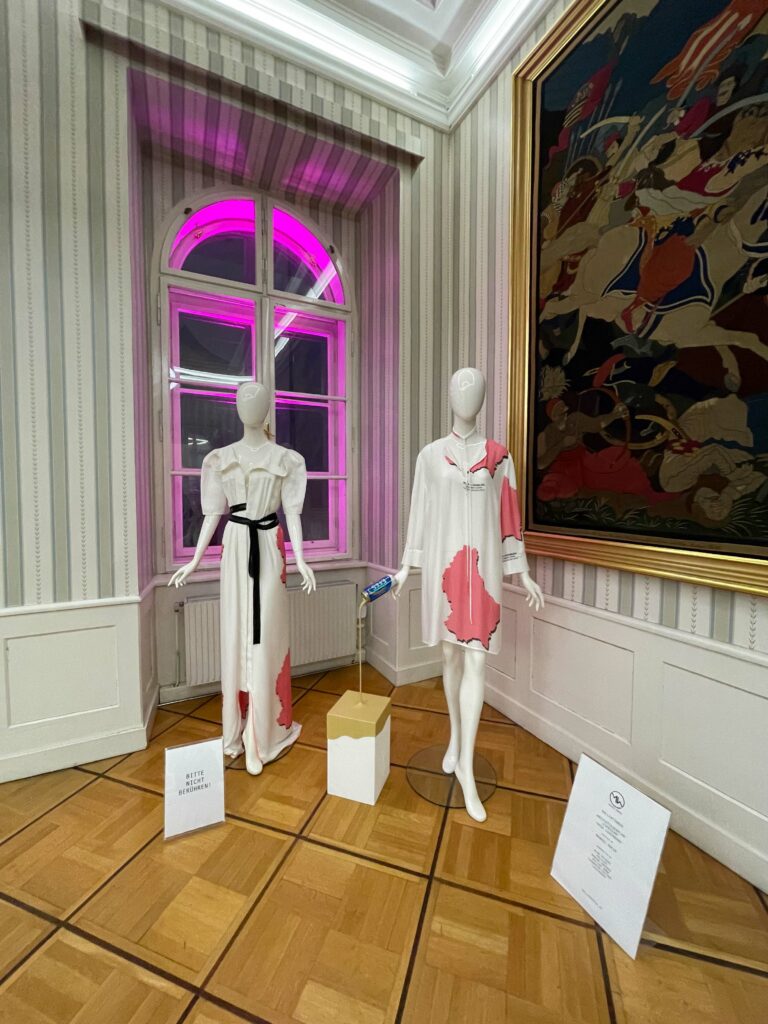

The main issue concerning the visible repair and resale of clothes Roth illustrated in her lecture is the uncertain legal status of reselling a visibly mended garment as a new or updated design under the name of the repairing designer. Roth highlights that for a long time, the goal of repairing was to make the repair process as invisible as possible. She mentioned brands like the luxury fashion house Hermès, who have a dedicated repair program for their bags. The goal of their repair strategy is to “reset” the products to their original state as well as possible, without leaving visible traces of the repair process. Roth postulates that the act of repair should be reconsidered as a creative act of its own which is allowed to leave traces. Through her example of a blouse however, she illustrates what the challenges for such a recontextualization can bring. In her performance, Roth visibly mended a blouse which was originally designed by Dries van Noten. If she wanted to resell the blouse as her own design, there would be a legal argument for copyright infringement because of the protections on the original design. The entire discussion went into more detail, illustrating that within fashion, copyright is a complicated question in general. Some aspects of fashion designs are protectable by copyright, like pattern designs. Certain other aspects however, cannot be protected by copyright, such as silhouettes for example. The copyright question does not come up when a garment is sold without visible mending manipulations as a second hand item attributed to the original designer, which begs the question – when does a repair become visible enough to be relevant and what are the rights of the visible mender in this process.

My impression of the talk was that this issue is certainly interesting and seems to be quite complicated. I personally do not quite see the visible repair of garments and the resale of them on a large scale as an issue that reach dimensions where it will really disrupt the fashion system. However, I of course have not done extensive research on this and can therefore only state my first impression and general opinion in this case.

As for the relevance to my research topic – I believe digital fashion faces a similar issue of copyright and especially ownership. These topics will be discussed further in a future regular blog post.

1Programm – Re:Pair Festival 10.-27.10.2024. October 27, 2024. Re:Pair Festival. https://repair-festival.wien/programm/?date=2024-10-27.

2FHNW. “Evelyne Roth.” Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.fhnw.ch/en/people/evelyne-roth.

Sources

“Evelyne Roth,” FHNW, accessed November 11, 2024, https://www.fhnw.ch/en/people/evelyne-roth.

Programm – Re:Pair Festival 10.-27.10.2024, October 27, 2024, Re:Pair Festival, October 27, 2024, https://repair-festival.wien/programm/?date=2024-10-27.

All Images © Helene Goedl 2024