The Detection of Emotions through Facial Expressions

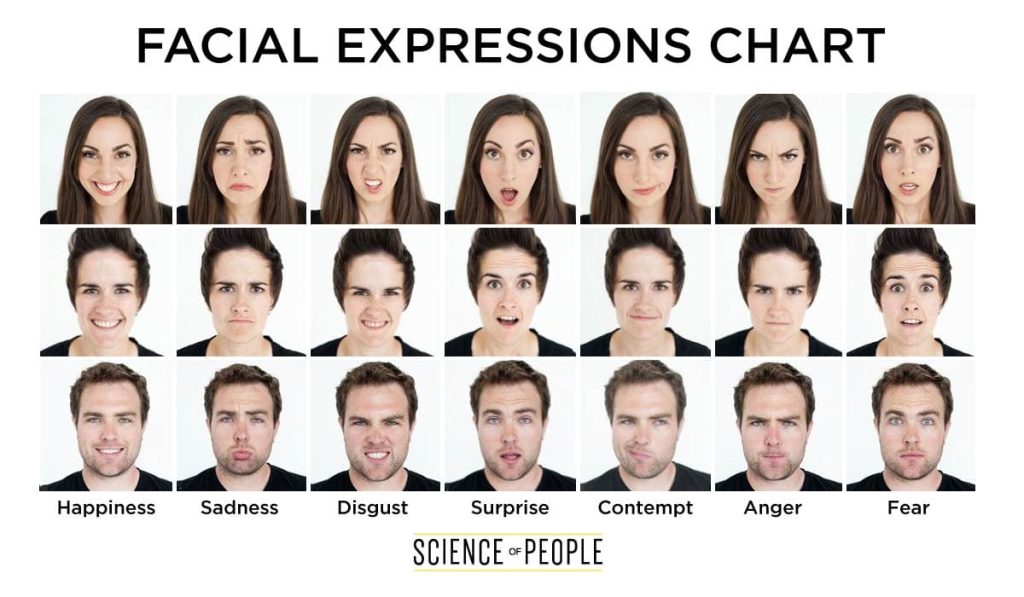

The ability to read and interpret facial expressions is crucial for understanding others, as it allows us to „anticipate other people’s most likely next actions“ (Julle-Daniere, 2019). In the 1970s, Paul Ekman and his colleagues demonstrated this universality by showing photographs of Western faces portraying one of the six primary emotions to an isolated tribe in Papua New Guinea. Their research confirmed that these essential facial expressions—anger, fear, happiness, disgust, sadness, and surprise—are recognized cross-culturally. These six primary emotions are „innate and universal“ to all humans, while secondary emotions tend to be more influenced by cultural factors and lack the „prototypical, universal facial expressions“ of primary emotions. Unlike primary emotions, which can often be assessed through physiological changes like an elevated heartbeat, detecting secondary emotions relies solely on self-reporting from the individual.

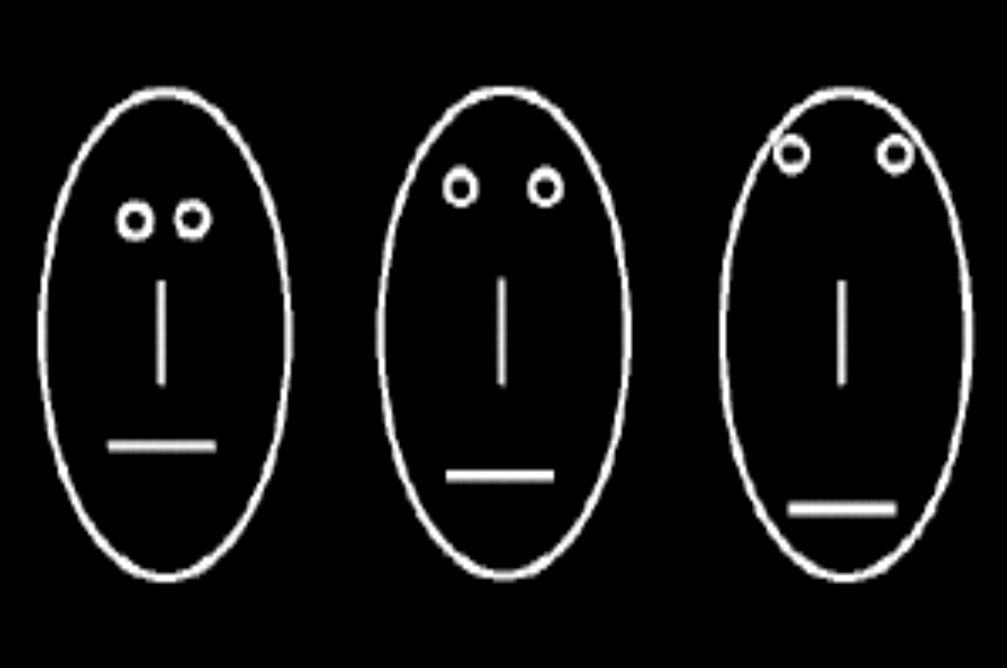

In 1938, Brunswik and Reiter conducted notable research on the general perception of facial expressions. They created a „graphic, schematized normal human face“ (American Psychological Association, 2023), where proportions could be systematically altered, such as eye width, forehead height, mouth position, and nose length. By showing 189 different variations of this face to 10 subjects, who then „rank-ordered their preferences,“ the researchers identified seven pairs of opposite judgments. These pairs include:

- Happy-Sad

- Young-Old

- Good-Bad

- Symmetric-Asymmetric

- Beautiful-Ugly

- Intelligent-Unintelligent

These impressions highlight the most common ways people perceive facial features and represent an early effort to categorize emotions by associating them with specific facial configurations.

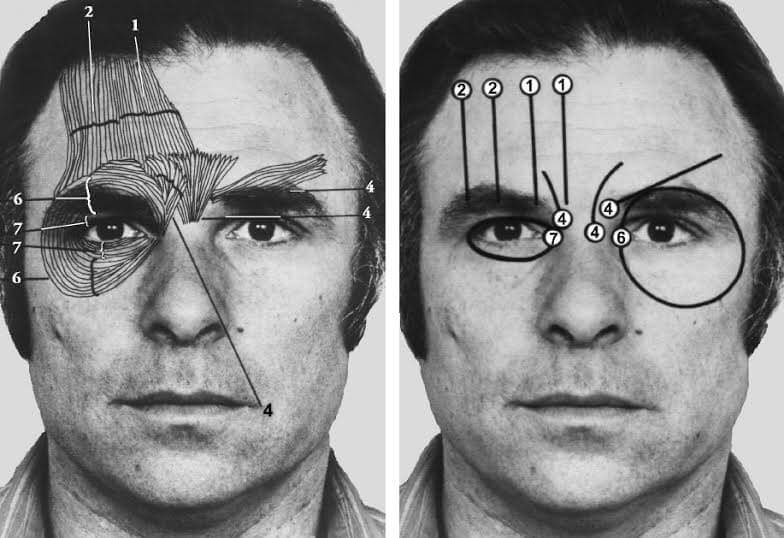

To enhance the precision of this categorization, Ekman and Friesen developed the Facial Action Coding System (FACS) in 1978. This method is based on a detailed analysis of the „anatomical basis of facial movement“ (American Psychological Association, 2023) and enables researchers to describe any facial movement in terms of specific „anatomically based action units“ (AUs). The system captures „subtle differences in appearance resulting from various muscle actions,“ providing a comprehensive tool for analyzing „visually discernible facial movements.“

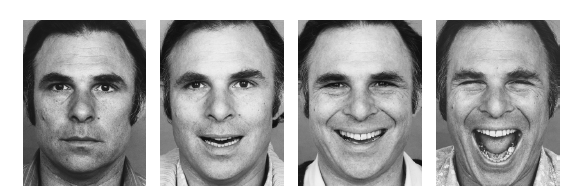

Today, the study of microexpressions has garnered significant attention. Microexpressions are defined as „very brief, involuntary facial expressions that humans make when experiencing an emotion“ and typically last between 0.5 and 4.0 seconds (Van Edwards, 2023). First discovered by Isaac Haggard and Dr. Paul Ekman, these fleeting expressions are considered impossible to fake. Various microexpression training programs have since emerged, promoting face decoding as „one of the best people skills you can have.“ Ekman identified seven key facial expressions—surprise, fear, disgust, anger, happiness, sadness, and contempt—as universally recognizable. Learning to interpret these microexpressions can be incredibly useful for understanding the emotions of those around us.

The example of surprise

- For example, the expression of surprise involves several specific facial cues:

- Raised and curved eyebrows

- Stretched skin below the brow

- Horizontal wrinkles across the forehead

- Widely opened eyelids with the white of the eyes visible above and below the iris

- A dropped jaw with parted teeth, but without tension or stretching of the mouth

Such indicators are not only valuable for understanding emotions but also for practical applications. For instance, when someone is attracted to you, they may give a brief „eyebrow flash,“ a quick raise of the eyebrows. Conversely, detecting contempt—where one side of the mouth is slightly raised—might help avoid conflicts in personal or professional relationships, such as preventing a divorce or work termination.

In conclusion, learning to read microexpressions is a valuable skill that is both „easy to learn and extremely useful in both professional and social life.

Sofie Neudecker, 27.11.2023

Sources.

The Faces of Emotions: Are they Universally or Culturally Varied? Psychology Today. Julle-Daniere, Eglantine, 2019. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/talking-emotion/201909/the-faces-emotions

Facial Action Coding System. Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1978). American Psychological Association, 2023. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft27734-000

Facial Action Coding System. PaulEkmanGroup, 2023. https://www.paulekman.com/facial-action-coding-system

http://system/#:~:text=The%20Facial%20Action%20Coding%20System%20%28FACS%29%20is%20a,components%20of%20muscle%20movement%2C%20called%20Action%20Units%20%28AUs%29.

Brunswik, E., & Reiter, L. (1938). Eindrucks-Charaktere Schematischer Gesichter (Impression Characteristics of Schematized Faces). Zeitschrift für angewandte Psychologie und Charakterkunde, 142, 67-134. American Psychological Association, 2023.

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1939-02434-001

The Definitive Guide to Reading Microexpressions (Facial Expressions). Body Language. Science of People. Vanessa Van Edwards, 2023.

https://www.scienceofpeople.com/microexpressions/