Design.tv / IMAGE RECEPTION INTERFERENCES – Transfers of Photography in Design 1960–1990 (Croatia)

I visited this exhibition two years ago, but I recently came across a YouTube video that offers a full explanation of it. What’s interesting is that one of the featured designers, Duško Bekar, makes an appearance in the video.

The exhibition’s curator, Marko Golub, mentions:

„The relationship between graphic design and photography is a very broad topic. Photography is used extensively in graphic design.“

But this exhibition doesn’t just explore the relationship between graphic design and photography—it also delves into the media processes that happen between the two.

Here are some of the most interesting works featured in the exhibition:

1. Boris Bućan

Bućan’s works often focus on self-referentiality, where the design reflects on itself. For example, one poster visually suggests the concept of photography through its own design (like the edges of the poster mimicking a photograph).

Bućan’s collaboration with Mihajlo Arsovski also stood out. They were among the most creative and provocative figures in graphic design at the time. One of Bućan’s posters for an Arsovski exhibition uses a photo of a billboard for posters—but ironically, none of the posters on the billboard are by Arsovski.

2. Željko Borčić

Borčić plays with the concept of “an image within an image,” creating a self-referential design.

3. Duško Bekar

Bekar’s work features abstract circular forms, created by shining a flashlight onto light-sensitive photo paper. Here, photography—normally used to capture reality—is turned into a tool to create something abstract.

4. Boris Ljubičić

The main poster for the 8th Mediterranean Games in Split (1979) showcases a bold MIS ’79 logo on a gradient blue background. Interestingly, this gradient wasn’t created digitally (computers weren’t widely used in design back then). Instead, Ljubičić used a photographic trick—deliberately blurring two Pantone blue color swatches to create the gradient effect.

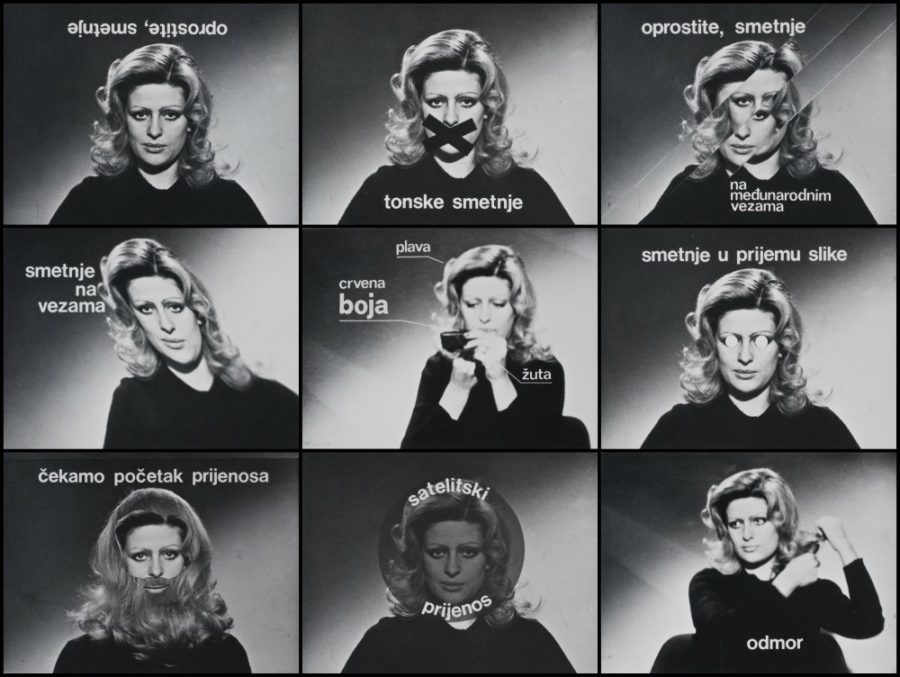

5. Sanja Iveković & Dalibor Martinis

This duo experiments with the visual distortions typical of television screens, playing with the imperfections and glitches of electronic media.

Across the exhibition, you’ll notice how designers use photography in diverse ways—sometimes multiplying a single image in a “pop art” style, other times layering a series of photos to create cinematic effects. Photography itself is also explored in a variety of genres, from documentary and portrait photography to artistic experiments using techniques like high-key lighting, double exposures, wide-angle lens distortions, solarization, and more.

Two key magazines from the period, Danas and Polet, were also crucial in showcasing these creative intersections of design and photography.

This exhibition offers a fascinating glimpse into how photography and graphic design interacted during this period, featuring works by designers like Ivan Picelj, Mihajlo Arsovski, Boris Bućan, Boris Ljubičić, Mirko Ilić, Gorki Žuvela, Dalibor Martinis, Goran Trbuljak, Sanja Iveković, Sanja Bachrach Krištofić, and Greiner & Kropilak. It also highlights contributions from photographers like Luka Mjeda, Ante Verzotti, Slobodan Tadić Tec, Željko Stojanović – Žika, Boris Cvjetanović, Mario Krištofić, and many others.