Emerging technology, the development of novel printing techniques, and an increased desire to provide materials for individuals with varying needs and abilities have all contributed to an increase in the desire to create tactile representations. It is well-known that sight and touch operate on very separate levels, resulting in significantly different ways of experiencing the world. Sight is a passive, instantaneous perception, while touch is dynamic and sequential (Lopes, 1997).

Touch has lower resolution compared to vision, with receptors spread across the body. Tactile reading in public is limited to hands, often using a single index finger, making vision relatively superior in simultaneously processing layers of information. Apprehending information and recognizing visuals by touch is more slower than it is by sight, demands a higher level of cognitive maturity, and puts a greater strain on a person’s memory. Finally, research into shape identification reveals that it is rare for certain shapes and details (for example, acute, obtuse angles) to be differentiated through touch.

It is crucial to keep in mind that visual impairment is heterogeneous, meaning that different people have different degrees of sight and will experience different stages of vision loss throughout their lives. While some people may have seen a great deal in their lifetime, others may have seen nothing at all. In addition, people’s motivations to touch can vary depending on context and culture (e.g., how much they have been encouraged or discouraged to touch things). As a result, people may have varying levels of experience using touch to explore their surroundings (Strickfaden, & Vildieu, 2014)..

In the journal Lopes argued that pictures aren’t exclusively visual (1997): ”We have made two mistakes. The first lies in defining pictures as essentially visual. The picture-interpretation and drawing skills of congenitally and early blind people show that this mistaken… But if, as I have argued, pictures are not exclusive representations, then this argument topples and there is no reason that pictures‘ aesthetic properties are only visual and must be apprehended by using our eyes. A new possibility opens up before us. Art is in the business of exploring and expanding its own boundaries, and tactile pictures are terra incognita.”

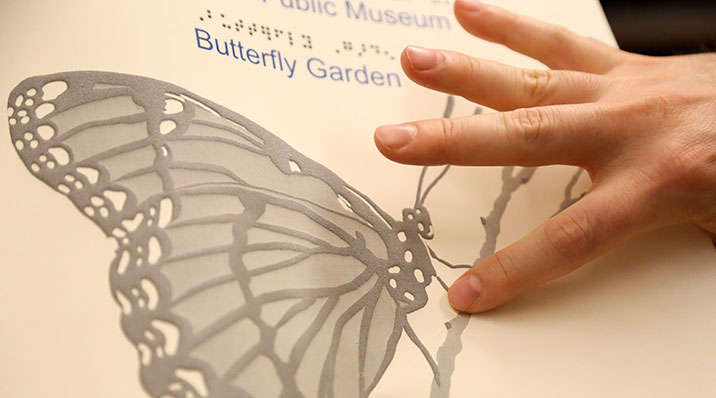

One challenge in communicating through tactile images is the decline in touch sensitivity with age, varying among individuals based on experience and education. Striking a balance is crucial in designing tactile layers – they should be explicit enough to convey details without oversimplifying to the point of diminishing cognitive engagement. Textural elements like cross-hatching, smooth areas, and rough surfaces contribute to contrast within a tactile image, aiding in the differentiation of materials or figures. This contrast is pivotal for comprehension. Establishing a focal point is essential for tactile exploration, achieved by using thicker materials or incorporating high-contrast elements. Unlike vision, where faces or color contrast draw attention, touch is drawn to contrasting tactile elements. The focal point in touch can begin anywhere on the composition, emphasizing the importance of adding contextual information, such as audio, after creating the image.

Individuals‘ ability to recognize tactile elements varies, regardless of sight. Tactile image comprehension depends on the willingness to engage with touch, especially for visually impaired individuals who rely on abstracting concepts. Users must correlate audio or textual descriptions with the tactile experience. Crafting touch-supportive artifacts requires careful consideration for enhanced understanding. While transforming visual artifacts into perfect tactile replicas is impossible, capturing specific attributes in a tactile form can represent key aspects of the original (Strickfaden, & Vildieu, 2014).

When thinking about tactile images, into consideration should be taken the following: first, the success rate for recognizing pictures by touch is much lower than it is for vision. Second, some pictures are more frequently recognized than others. Third, there is also some variation from individual to individual: while some blind people recognized many images others recognized few (Lopes, 1997).

Sources:

- Dominic M. M. Lopes. (1997). Art Media and the Sense Modalities: Tactile Pictures. The Philosophical Quarterly (1950-), 47(189), 425–440. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2956276

- Strickfaden, & Vildieu. (2014). On the Quest for Better Communication through Tactile Images. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 48(2), 105. doi:10.5406/jaesteduc.48.2.0105