From the Middle Ages through the Renaissance towards Modernity

Medieval art reflects how humans defined their place in a world dominated by the Church and Christian doctrine. In the depiction of the 12 apostles on the altar frontal from La Seu d’Urgell, all faces are schematic and geometric, lacking individual features. This uniformity mirrors the medieval worldview, where individual fulfillment was insignificant compared to one’s service to the Church and God. There is no attempt at realism here; faces lack shadows and half-tones, and the apostles‘ proportions are distorted, emphasizing the religious symbolism over physical accuracy.

The apostles are shown in profile, all gazing toward Christ, the central figure who alone faces the viewer. The use of halos around each apostle’s head, defined by simple black outlines, underscores their spiritual dedication, rather than their individuality. The overall composition is repetitive and geometric, indicating that what is depicted is not the physical world but an inner, religious vision shaped by faith. It is a reflection of a non-scientific worldview, where spiritual meaning took precedence over material representation.

The Renaissance: A Turn Towards Realism

„So I, Albrecht Dürer from Nuremberg, painted myself with true colors at the age of 29.“

— Albrecht Dürer, 1500

In the Renaissance, the dominance of Christian ideology waned, giving way to humanism and a revival of scientific thought that had been developed in antiquity but suppressed throughout the Middle Ages. This intellectual shift is evident in Renaissance art, where artists began to seek fulfillment not in divine service, but within themselves as individuals.

Albrecht Dürer’s self-portrait is a prime example of this transformation. In his 1500 Self-Portrait in Fur Coat, Dürer places himself at the center of the composition, directly facing the viewer in a manner reminiscent of how only Christ was depicted in medieval art. His hand gesture, echoing a blessing (Segensgruß), suggests that Dürer saw himself as a secondary creator, echoing divine creativity, yet still acknowledging his faith.

This portrait, however, also serves as self-promotion, revealing Dürer’s awareness of his role as an artist. Artists of the Renaissance no longer viewed themselves as mere craftsmen but as creators of genius, capable of divine-like mastery. Dürer’s portrait is rendered with meticulous realism, with details like the fine shading of his face and individual eyelashes bringing his likeness to life. The dark background ensures that his features stand out, emphasizing the importance of the individual, a stark contrast to medieval depictions of faceless collectives.

Modernity: A Shift Away from Realism – Art Nouveau and Early Abstraction

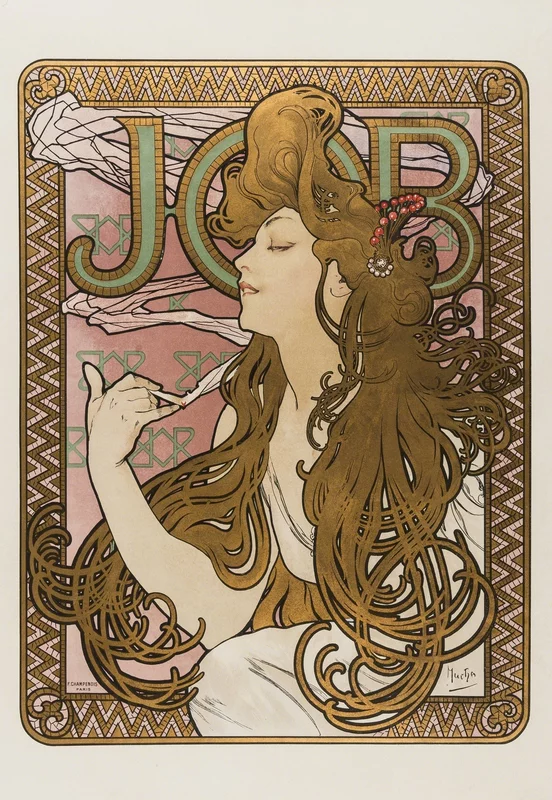

By the turn of the 20th century, the focus shifted once again, this time away from the realism of the Renaissance. The Art Nouveau period, which can be seen as a transitional phase toward modern art, mixed elements of realism with abstraction. A prime example of this transition is Alphonse Mucha’s 1896 poster for cigarettes. While the face still retains realistic details like shading and form, the thick black contour separating it from the decorative, repetitive background introduces a stylization that moves away from pure realism.

Similarly, Koloman Moser’s cover for Ver Sacrum (1899) maintains accurate proportions and realistic shading but simplifies these into harsh contrasts, with minimal use of half-tones. The curvilinear forms of the hair, intertwined with decorative flowers, exemplify the playful and ornamental spirit of the period.

The Viennese Secession and the Move Towards Geometry

By the time of the Viennese Secession, this decorative playfulness evolved further. Artists like Koloman Moser and Berthold Löffler reduced natural, curvy forms into more geometric shapes, creating precise patterns where individual features were often subsumed into the overall design. Faces, rather than standing out from their surroundings, became part of a larger repetitive composition. This move towards abstraction signified an increasing detachment from the realistic portrayal of the individual, favoring a more symbolic and decorative interpretation of human figures.

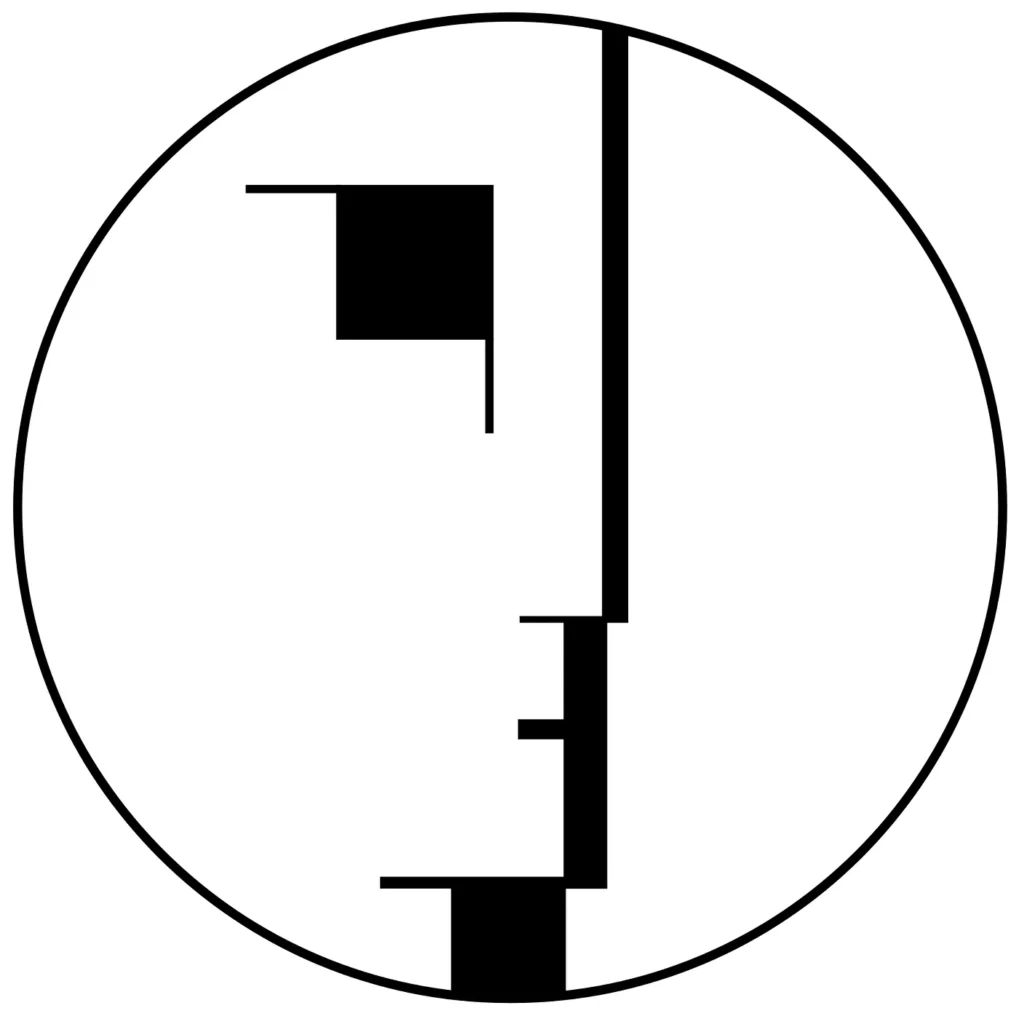

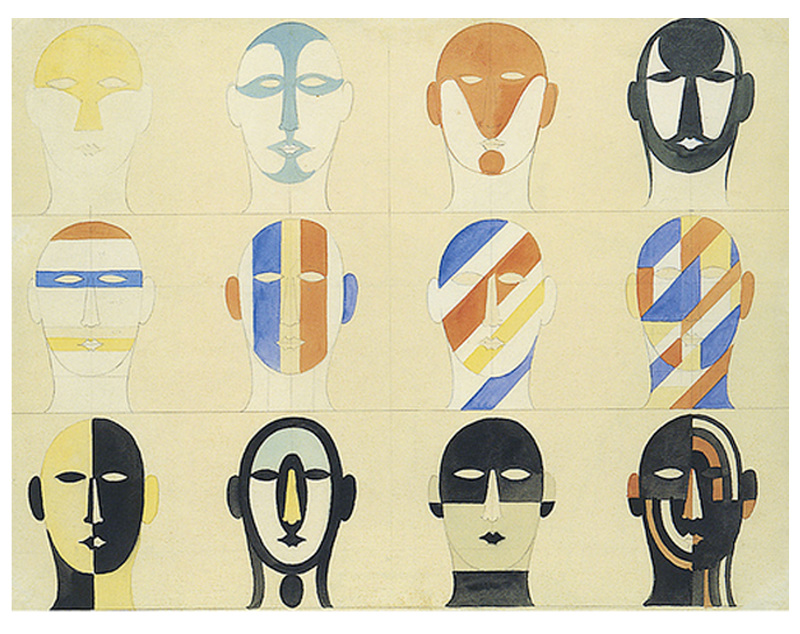

Bauhaus and the Essence of Form – Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus Influence

“Schlemmer played with primary shapes and the human form, reducing faces to their core elements in a conscious and minimalist approach.”

— Eric Roinestad

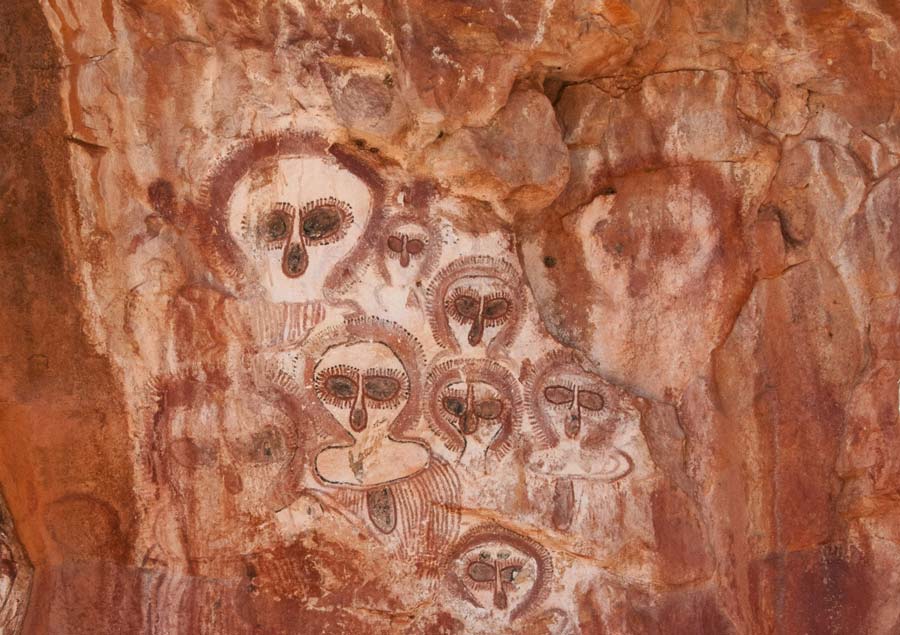

The Bauhaus, one of the most iconic movements of modern art, pushed the abstraction seen in Art Nouveau and the Viennese Secession to its logical extreme. Oskar Schlemmer, a key figure in the movement, explored the reduction of human forms to their most basic geometric elements. His minimalist compositions maintained expressive power despite their simplicity, demonstrating how even the most reduced forms could evoke emotion and meaning.

In this period, artists like Schlemmer moved away from depicting realistic likenesses, instead opting for simplified forms that reflected a more abstract understanding of human identity. By reducing faces to their core elements, modern artists like Schlemmer reconnected with the early abstraction seen in prehistoric cave paintings, though now with a fully conscious understanding of artistic creation.

Conclusion: The Cyclical Nature of Art

Throughout art history, two parallel processes have unfolded: the pursuit of realism and the search for internal images that express individual interpretation. From the abstract and symbolic art of the Middle Ages to the hyper-realism of the Renaissance and the abstraction of the modern era, these artistic movements reveal humankind’s ongoing exploration of identity and existence. Both approaches—realism and abstraction—are valuable and essential in understanding the complex evolution of human self-perception.

Sources:

Altar frontal from La Seu d’Urgell or of the Apostles. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://youtu.be/L2T2vXjr3Tw?feature=shared.

Tuschka, Alexandra. “Albrecht Dürer – Selbstbildnis im Pelzrock.” The Art Inspector, 2023.

https://www.the-artinspector.de/post/albrecht-dürer-selbstbildnis-im-pelzrock.

Peasley, Aaron. “The Legacy of Oskar Schlemmer.” The Present Tense, 2018.

https://present-tense.thefutureperfect.com/articles/oskar-schlemmer.

Müller, Jens. The History of Graphic Design. Juli.

Images:

Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait in Fur Coat, 1500, oil on panel, 67.1 x 48.9 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich,

https://www.the-artinspector.de/post/albrecht-dürer-selbstbildnis-im-pelzrock.

https://artchallenge.world/gallery/it/35

Altar Frontal from La Seu d’Urgell, 12th Century. Web Resource, accessed October 10, 2024. https://sc26c7b0z32465y9232634112bda93d66.s3.amazonaws.com/web/index.html?js=26w4871135j64224887828910428182/a26w4p325n5e3t3499910558b7fedb9_ca.json.

Alphonse Mucha, La Belle Époque, poster, 1896, CZ/FR, accessed October 10, 2024,

https://clarkfineart.com/artists-catalog/la-belle-epoque/.

Moser, Koloman. Magazine Cover. 1899. AT. Accessed October 10, 2024.

https://www.posterlounge.it/p/514808.html.

Schlemmer, Oskar. 1922. DE. Accessed October 10, 2024.

https://it.pinterest.com/pin/913245630674485931/.

https://it.pinterest.com/pin/452822937503839795/.