Feedback

This week was all about feedback. After months of deep diving into research, I had the chance to discuss my master’s thesis progress with three different experts, each offering a unique perspective on my work. These conversations helped me reflect on where I am, what I’ve accomplished so far, and most importantly where I should go next.

First Round: Structuring the Next Steps

On Wednesday, I had a meeting with Ms. Ursula Lagger, who guided us through our master’s thesis proseminar this semester. Our conversation focused on my exposé, my current research state, and my plans moving forward. While I have already done a lot of research on the theoretical background, she emphasized that now is the time to shift towards the practical aspects of my work. One of the biggest takeaways from this meeting was the importance of structuring my prototyping phase. She encouraged me to make a clear plan on how and when I will move from expert interviews to practical examples, prototyping, testing, and iteration. Given the timeframe of our thesis, having a structured roadmap will help me stay on track and make the most of the time I have left. This feedback was a great reminder that while research is essential, it needs to be paired with practical application.

Second Round: Expanding My Perspective

Thursday’s meeting with Mr. Horst Hörtner from Ars Electronica Futurelab provided a completely different perspective. We talked about my passion for universal design, which has been a key motivation behind my thesis. He introduced me to companies that develop products for the medical field and have successfully conducted medical trials, as well as projects designed with autistic people in mind. Beyond technical guidance, he gave me valuable pointers on how to approach expert interviews and tell the story behind my research. He encouraged me to clearly define why this field of design is important to me and how my work connects to real-world problems. This discussion gave me a lot of insights into the bigger picture of universal design, showing me new opportunities for research and development in this space. More than that, it reinforced the importance of being passionate about what I’m designing.

Third Round: Bringing Ideas to Life

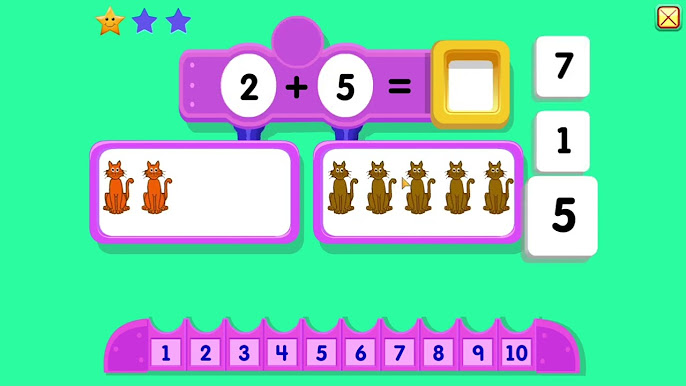

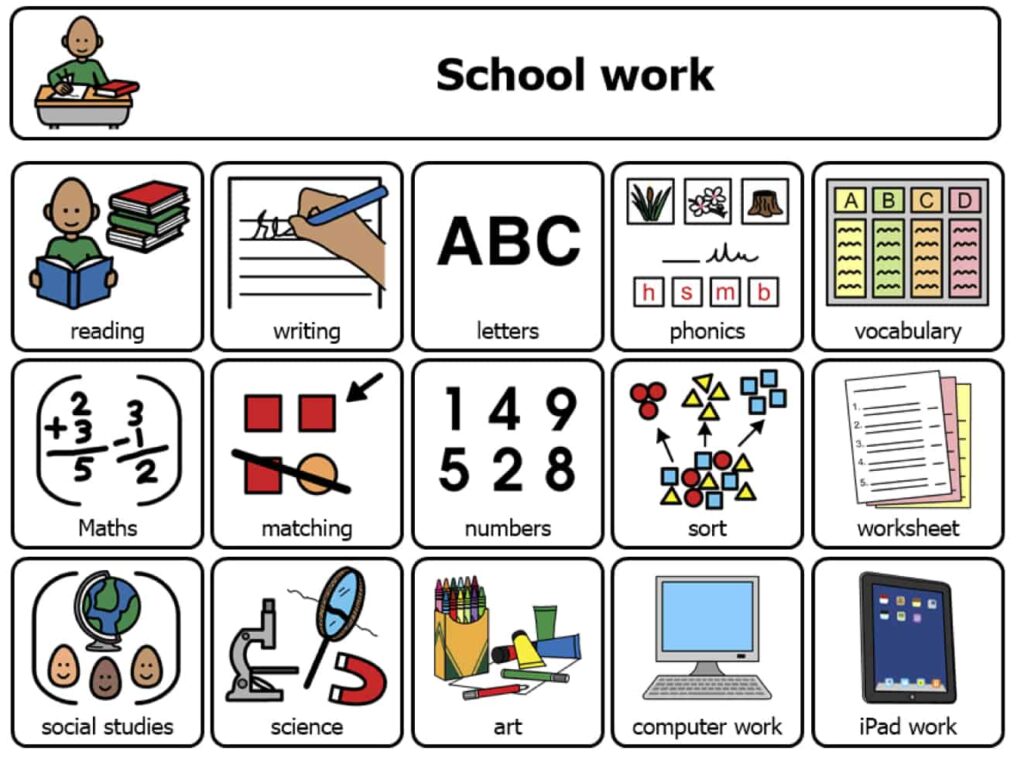

Today, I had a meeting with Mr. Kaltenbrunner from the University of Art and Design in Linz, who is also a co-founder of Reactable Systems, one of the inspirations for my last year’s prototype for design and research. Our conversation revolved around tangible user interfaces and how they could be used for children with autism. He showed me several existing projects for autistic children, which immediately reignited my interest in creating an interactive school table. We talked about the best way to start working on this idea, and he suggested that my first focus should be on designing the UI for the interface, essentially starting with a digital app before thinking about how to integrate tangible interaction. One concept that stood out from our discussion was fictional design, a method that encourages focusing on the concept and complexity of interactions first, rather than getting stuck on the technological limitations. Given the limited timeframe of my thesis, this approach makes a lot of sense. Instead of trying to perfect the hardware immediately, I should develop the experience and interactions first, then later explore how to make them tangible. This conversation was incredibly valuable because it helped me redefine my next steps. Instead of jumping straight into prototyping the hardware, I will first develop the digital interface, refine the user experience, and then gradually explore physical interactions.

These three rounds of feedback helped me gain clarity on my direction. Moving forward, I now have a clear structure for my thesis work:

- Finalize my research phase by conducting a few more expert interviews, now with a clearer understanding of what insights I need.

- Develop a structured plan for my prototyping phase, breaking it down into manageable steps.

- Start with digital prototyping, designing an interactive learning tool that can later be explored for tangible interaction.

- Use the concept of fictional design to refine my ideas, focusing on how the experience should feel before worrying about the technical aspects.